By Hassan Jan

British imperialism throughout its history in the quest for its expansion and imperial designs had carved out many new states and statelets by drawing artificial and reactionary lines and frontiers thus splitting indigenous civilizations of thousands of years. Though the grandeur of British imperialism has been dumped into the dustbin of history but the cleavage lines it drew have subjected these regions to an eternal inferno of conflicts and wars. The Middle East was dissected through the notorious Sykes-Picot agreement between France and Britain. British Raj ripped up the South Asian Sub-continent through Radcliff and Durand lines. All these frontiers were drawn for plunder of the resources of these lands and to subjugate the populace under the ancient Roman dictum of Divide and Rule.

During the nineteenth century, Tsarist Russia and Britain were locked in a rivalry for influence in Central Asia, Afghanistan and South Asian subcontinent commonly known as “The Great Game”. Russia was slowly spreading its tentacles to Central Asia and had already annexed many Central Asian Khanates and Britain feared that Russia would expand its empire to include Afghanistan and reach the “warm waters” of Indian Ocean and from there would invade the British Indian subcontinent, the ‘jewel in the crown’ of British Empire. The Emir of Afghanistan Dost Mohammad had recently lost his winter capital Peshawar to the Sikh Empire in 1834. He tried to recapture it several times but failed miserably. In 1837, Jan Prosper Witkiewicz, Russian diplomat, was sent to Kabul to meet Emir Dost Mohammad. This was perceived in London as Dost Mohammad might be seeking help from Russians and to form a military alliance to recapture Peshawar. This fear prompted the British Raj to invade Afghanistan in 1839 to forestall Russian expansion to the country.

First Anglo-Afghan War 1839-1842

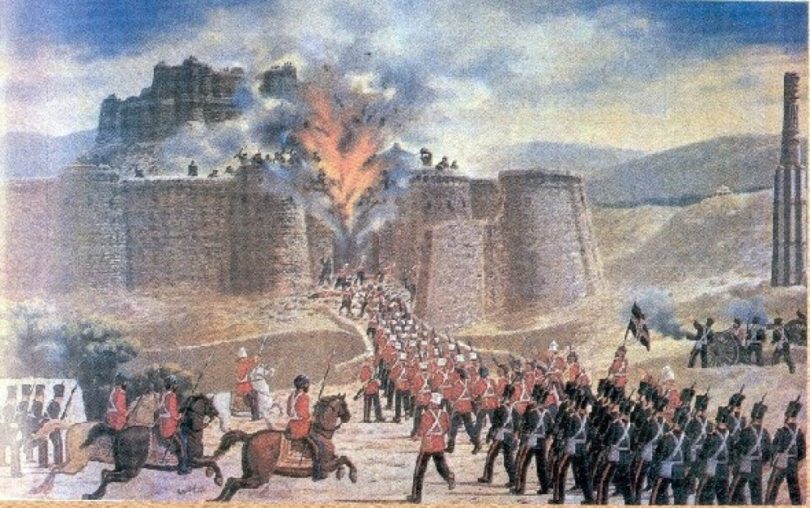

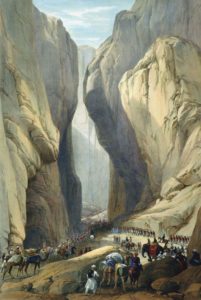

In 1838, British East India Company (which was granted the right to rule India by the British crown) amassed an army of 21,000, which comprised mainly upon Indian soldiers. This “Army of the Indus” started to march from Punjab in December 1838. After crossing the Bolan Pass, they reached Quetta in March 1839. They swiftly captured Quetta and Kandahar and in July of that year ousted Dost Mohammad Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan and installed Shah Shuja Durrani as the new puppet Emir. The great Marxist teacher Frederick Engels wrote, “The Bolan Pass was traversed in March; want of provisions and forage began to be felt; the camels dropped by hundreds, and a great part of the baggage was lost. April 7, the army entered the Khojak Pass, traversed it without resistance, and on April 25 entered Kandahar, which the Afghan princes, brothers of Dost Mohammed, had abandoned. After a rest of two months, Sir John Keane, the commander, advanced with the main body of the army toward the north, leaving a brigade, under Nott, in Kandahar. Ghazni, the impregnable stronghold of Afghanistan, was taken on July 22. A deserter having brought information that the Kabul gate was the only one that had not been walled up; it was accordingly blown down, and the place was then stormed. After this disaster, the army Dost Mohammed had collected, at once disbanded, and Kabul too opened its gates on August 6, 1839. Shah Shujah was installed but the real direction of government remained in the hands of McNaughton, who also paid all Shah Shujah’s expenses out of the Indian treasury.”

After this swift military victory, the British withdrew much of their troops and left behind 6,000 troops to prop up Shah Shujah’s regime. Everything was going smoothly and calm as reported by the political agent William McNaughton to the governor-general of British India, Lord Auckland. Sporadic rebellions were raising heads throughout the country but were crushed. But beneath the surface, there was a simmering revolt that was soon to erupt against the British occupation. Then came the fateful day when the Afghan rebels led by Wazir Akbar Khan, the son of the deposed Emir Dost Mohammad, stormed the cantonment in Kabul, housed by the British, killing Captain Alexander Burns and his aides. The British tried to soothe the rebels and end the siege of the cantonment by offering Wazir Akbar Khan the post of Wazir of Afghanistan. Meanwhile, the British had hatched a conspiracy with other tribal chieftains to assassinate Wazir Akbar Khan. When he became aware of this double game, he called on William Macnaghten for negotiation and during the negotiation Wazir Akbar Khan killed him by shooting a pistol placed in his mouth. His bravado inspired other Afghans and the rebellion that erupted into a full-blown insurrection.

With no end to the siege of the cantonment in Kabul, the British negotiated with Wazir Akbar Khan to let them go and provide a safe passage to Jalalabad. Wazir agreed. The British forces along with their camp followers left Kabul for Jalalabad. But the Afghan tribesmen massacred the entire convoy of British troops led by William Elphinstone during this voyage.

Fredrick Engels would later describe in 1857; “The British marched out, 4,500 combatants and 12,000 camp-followers. One march sufficed to dissolve the last remnant of order, and to mix up soldiers and camp followers in hopeless confusion, rendering all resistance impossible. The cold and snow and the want of provisions had similar impacts as in Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow [in 1812]. But instead of Cossacks keeping a respectful distance, infuriated Afghan marksmen, armed with long-range matchlocks, occupying every height, harassed the British. The chiefs who signed the capitulation could not restrain the mountain tribes. The Koord-Kabul Pass became the grave of nearly the military force that has launched its campaign in Afghanistan. The small remnant with less than 200 Europeans, fell at the entrance of the Jugduluk Pass. Only one man, Dr. Brydon, reached Jalalabad to tell the tale. Many officers, however, had been seized by the Afghans and kept in captivity, Jalalabad was held by Sale’s brigade. The capitulation was demanded of him, but he refused to evacuate the town, so did Nott at Kandahar. Ghazni had fallen; there was not a single man in the place that understood anything about artillery, and the Sepoys of the garrison had succumbed to the climate.”

Shah Shuja was defenceless in Kabul without British troops, left on his own. The rebellious tribes killed him shortly. Dost Mohammad was released from captivity in India and reinstated as the Emir of Afghanistan. Thus ended the disastrous British adventure in Afghanistan.

Second Anglo-Afghan War 1878-1880

The defeat in the first Anglo-Afghan war continued to haunt the British Empire in the later decades. In 1878, a Russian diplomatic delegation was received in Kabul, which alarmed the British. They also demanded from the then Emir of Afghanistan Sher Ali Khan to allow a British envoy to be permanently settled in Afghanistan. Sher Ali Khan turned down Britain’s demand and refused to receive the delegation headed by Neville Bowles Chamberlain and vowed to stop them. In September 1878, Lord Lytton sent a diplomatic delegation to Kabul. When the mission reached Khyber Pass, they were stopped and returned. This proved to become a trigger for the second invasion of Afghanistan by the British.

This refusal to receive the British diplomatic mission infuriated the British Empire and also they perceived it as the increasing influence of the Russians on the regime in Kabul. The British amassed an army of about 40,000 troops, of which mostly were Indians. Bearing in mind the disastrous defeat at the hands of Afghans in the first Anglo-Afghan war about four decades earlier in 1842, this time the invasion was planned meticulously. Afghanistan was invaded from three different points. Three columns of troops moved in to infiltrate the country. The first and the largest column Peshawar Field Force entered from the Khyber Pass. The second column the Kurram Valley Field Force captured the Peiwar Kotal. The third column invaded Kandahar. The much superior British Indian army defeated the Afghan forces. The desperate Emir Sher Ali Khan went to Turkmenistan to appeal to the Russian Tsar for assistance but the Russians abstained due to their recent debacles in Europe. Sher Ali Khan died in February 1879. His son Yaqub Khan ascended to the throne.

The victorious British army grasped several geographical and political achievements through Treaty of Gandamak signed on 26 May 1879 between the Emir of Afghanistan Mohammad Yaqub Khan and Sir Louis Cavagnari, the British representative. Under the treaty, Afghanistan ceded its control on foreign affairs to British Raj in India and allowed a permanent British mission to reside in Kabul. It lost several frontier areas including Kurram and Pishin Valleys, Sibi district and the Khyber and Michni Passes to the British. The British imperialists wanted to use these captured areas as a buffer against any future infringement of Russian Tsarist Empire on the British Indian subcontinent.

Durand Line

The treaty of Gandamak was a humiliating treaty to the Afghans. There was a rebellion in Kabul in September 1879. Enraged troops of Emir’s army stormed the British mission in Kabul. Cavagnari and his aides were massacred. However, the uprising was ultimately crushed. The British forced Yaqub Khan to abdicate and install his cousin Abdur Rahman as the new puppet Emir of Afghanistan in 1880. Abdur Rahman ratified the Gandamak Treaty.

In 1893, Mortimer Durand, the then foreign secretary of British India was sent to Kabul. The purpose of this visit was to further solidify the gains made through the Treaty of Gandamak and to permanently deprive Afghanistan of the areas captured during the second Anglo-Afghan war. Mortimer Durand was assigned the task of delineating the borders between Afghanistan and the British India. Under the agreement, half of the Pashtun areas were included and made part of the British India while the other half of the Pashtun areas remained in Afghanistan’s domain. The boundary thus cleaved through the mainly Pashtoon and Baloch tribes dividing them between Afghanistan and the British Indian subcontinent.

The British imperialists had executed their imperialist designs in a most cunning way. As Bijan Omrani has pointed out;

“There were advantages of the Line for the British. There was a strategic advantage in that they held positions on the frontier passes and controlled the heights, thus facilitating the policing of the passes. They also managed to achieve the tripartite border – a vision they had held for a long time. The first part of the border was the buffer state, Afghanistan. The second part was the tribal areas in the hills, which the British did not try to govern, but simply garrisoned. These areas were vassal states, on the Indian side of the line but not under the sovereignty of British India. The third part was further back, where the real government of India started. The depth of this frontier system certainly kept the Russians away, but the corollary was that the British faced the familiar internal policing problem.” (The Durand Line: History and problems of the Afghan-Pakistan border, 2009)

By the time of third Anglo-Afghan war in 1919, Afghanistan got complete independence from Britain but the Durand Line agreement remained intact and was further ratified by King Amanullah Khan under the Treaty of Rawalpindi in 1919. The partition of Indian subcontinent in 1947 along religious lines by drawing another bloody frontier called The Radcliff line further complicated the geopolitics of South Asian subcontinent and started an era of decades of unending wars and conflicts. The reactionary nature of these artificial boundaries started to unravel once the British ruler relinquished the South Asian subcontinent to the native rulers.

Durand Line divided the Pashtoon peoples into two countries. Contrary to the common perception, this reactionary line also divided and ripped up the Baloch. Thousands of years of common culture and civilizations were torn apart. This line is a constant source of conflict and instability in the region. The reactionary states of the region use these artificial borders for the perpetuation of their rule. As long as these borders persist, the region would continue to be in a state of continuous turmoil. Above all, the capitalist states of this region need these frontiers for their survival. Only through a revolutionary overthrow of these capitalist states, these artificial frontiers can be abolished.