By Michael Löwy

Eighty years ago, in August 1940, Leon Davidovich Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico by Ramon Mercader, a fanatical agent of the Stalinist GPU. This tragic event is widely known today, well beyond the ranks of Trotsky’s supporters, thanks, among other things, to the novel The Man Who Loved Dogs by Cuban writer Leonardo Padura …

Revolutionary of October 1917, founder of the Red Army, infexible opponent of Stalinism, founder of the Fourth International, Leon Davidovich Bronstein made essential contributions to Marxist thinking and strategy: the theory of permanent revolution, the Transitional Programme, analysis of uneven and combined development – among others. His History of the Russian Revolution (1930) has become an indispensible reference: it was among the books of Che Guevara in the Bolivian mountains. Many of his writings can still be read in the 21st century, while those of Stalin and Zhdanov are forgotten in the dustiest shelves of libraries. One can criticize some of his decisions (Kronstadt!) and challenge the authoritarianism of certain writings of the years 1920-21 (such as Terrorism and Communism, 1920); but we cannot deny his role as one of the greatest revolutionaries of the 20th century.

León Trotsky was also a man of great culture. His little book Literature and Revolution (1924) is a striking example of his interest in poetry, literature and art. But there is one episode that illustrates this dimension of the character better than any other: the drafting, with André Breton, of a manifesto on revolutionary art. This is a rare document of “libertarian Marxist” inspiration. In this brief tribute to the anniversary of his death, let us recall this fascinating episode.

During the summer of 1938, Breton and Trotsky met in Mexico, at the foot of the Popocatepetl and Ixtacciuatl volcanoes. This historic meeting was prepared by Pierre Naville, ex-surrealist, leader of the Trotskyist movement in France. Despite a violent controversy with Breton in 1930, Naville wrote to Trotsky ’in 1938 recommending Breton as a courageous man who had not hesitated, unlike so many other intellectuals, to publicly condemn the infamy of the Moscow Trials. Trotsky had therefore given his agreement to receive Breton and the latter, with his companion Jacqueline Lamba, had taken the boat to Mexico. Trotsky was living at that time at the Blue House, which belonged to Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, two artists who shared his ideas and who had received him with warm hospitality (alas, they would fall out a few months later). It was also in this huge house located in the Coyoacan district that Breton and his companion were accommodated during their stay.

It was a surprising encounter, between personalities apparently located at the antipodes: one, a revolutionary heir to the Enlightenment, the other, installed on the tail of the romantic comet; one, founder of the Red Army, the other, initiator of the Surrealist Adventure. Their relationship was quite uneven: Breton had enormous admiration for the October revolutionary, while Trotsky, while respecting the courage and lucidity of the poet – one of the rare French left intellectuals to oppose Stalinism – had some difficulties understanding Surrealism… He had asked his secretary, Van Heijenoort, to provide him with the main documents of the movement, and Breton’s books, but this intellectual universe was foreign to him. His literary tastes led him to the great realist classics of the 19th century rather than to the unusual poetic experiences of the surrealists.

At first, the meeting was very warm: according to Jaqueline Lamba – Breton’s companion, who had accompanied him to Mexico, interviewed by Arturo Schwarz – “we were all very moved, even Lev Davidovich. We immediately felt welcomed. with open arms. LD was really happy to see André. He was very interested “. However, this first conversation almost went wrong … According to the testimony of Van Heijenoort: “The old man quickly began a discussion of the word surrealism, to defend realism against surrealism. He understood by realism the precise meaning that Zola gave to this word. He began to talk about Zola. Breton was at first somewhat surprised. However, he listened attentively and knew how to find the words to highlight certain poetic features in Zola’s work.” (Interview of Van Heijenoort with Arturo Schwarz). Other controversial subjects arose, notably on the subject of “objective chance” dear to the surrealists. It was a curious misunderstanding: while for Breton it was a source of poetic inspiration, Trotsky saw it as a questioning of materialism …

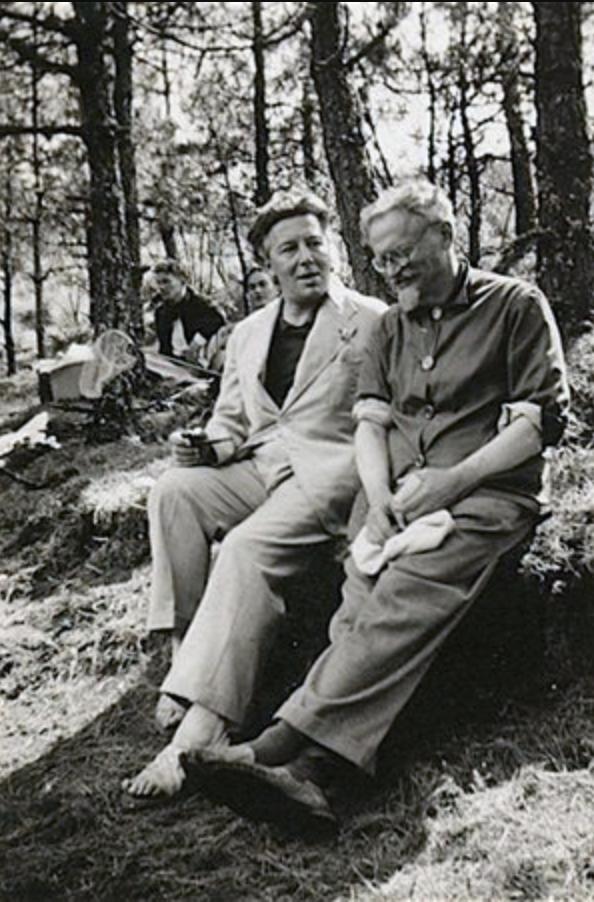

And yet, the moment passed, Russian and French finding a common language: internationalism, revolution, freedom. Jacqueline Lamba rightly speaks of an elective affinity between the two. Their conversations take place in French, which Lev Davidovich spoke fluently. They will travel Mexico together, visiting the magical places of pre-Hispanic civilizations, and, immersed in rivers, fishing. We see them conversing in a friendly manner in a famous photo, sitting close to each other in an undergrowth, barefoot, after one of these fishing trips.

From this meeting, from the friction of these two volcanic stones, a spark arose that still shines: the Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art. According to Van Heijenoort, Breton presented a first version, and Trotsky cut this text out by pasting his own contribution (in Russian). It is a libertarian communist text, anti-fascist and inimical to Stalinism, which proclaims the revolutionary vocation of art and its necessary independence from states and political apparatus. He called for the creation of an International Federation for Independent Revolutionary Art (FIARI).

The idea for the document came from Leon Trotsky, immediately accepted by André Breton. It was one of the few, if not the only jointly written document by the founder of the Red Army. The product of long conversations, discussions, exchanges, and no doubt some disagreements, it was signed by André Breton and Diego Rivera, the great Mexican muralist, at the time a fervent supporter of Trotsky (they will fall out soon after). This harmless little lie was due to the old Bolshevik’s belief that a Manifesto on Art should be signed only by artists. The text had a strong libertarian tone, notably in the formula, proposed by Trotsky, proclaiming that in a revolutionary society the artists’ regime should be anarchist, that is, based on unlimited freedom. Another famous passage in the document proclaims “any license in art”. Breton had proposed to add “except against the proletarian revolution”, but Trotsky proposed to delete this addition! We know André Breton’s sympathies for anarchism, but curiously, in this Manifesto, it is Trotsky who wrote the most “libertarian” passages.

The Manifesto affirms the revolutionary destiny of authentic art, that is, that which “sets up the powers of the inner world” against “the present, unbearable reality.”. Is it Breton or Trotsky who formulated this idea, undoubtedly drawn from the Freudian repertoire? It doesn’t matter, since the two revolutionaries, the poet and the fighter, managed to agree on the same text.

The document retains, in its fundamental principles, an astonishing topicality, but it does not suffer less from certain limits, due perhaps to the historical conjuncture of its drafting. For example, the authors strongly denounce the restrictions on the freedom of artists, imposed by states, particularly (but not only) totalitarian states. But, curiously, it avoids a discussion, and a criticism, of the obstacles which result from the capitalist market and the fetishism of the commodity… The document quotes a passage from the young Marx, proclaiming that the writer “must not in any case live and write just to earn money”; however, in their commentary on this passage, instead of analyzing the role of money in the corruption of art, the two authors limit themselves to denouncing the attempts to impose “constraints” and “disciplines” on artists in the name of “the national interest”. It is all the more surprising as one cannot doubt the visceral anti-capitalism of the two: had Breton not described Salvador Dali, as a mercenary, like an “Avida Dollars”? We find the same lacuna in the prospectus of the review of the FIARI (Clé), which calls for combating fascism, Stalinism, and … religion: capitalism is absent.

The Manifesto concluded, as we have seen, with a call to create a broad movement, a sort of International of Artists, the International Federation for an Independent Revolutionary Art (FIARI), including all those who recognized themselves in the general spirit of document. In such a movement, write Breton and Trotsky, “the Marxists can walk here hand in hand with the anarchists (…) provided that both of them implacably break with the reactionary police spirit, be it represented by Joseph Stalin or by his vassal Garcia Oliver.”. This call for unity between Marxists and anarchists is one of the most interesting aspects of the document and one of the most current, a century later.

In parentheses: the denunciation of Stalin, qualified by the Manifesto as “the most perfidious and the most dangerous enemy” of communism, was essential, but was it necessary to treat the Spanish anarchist García Oliver, the companion of Durruti, the historical leader of the CNT-FAI, the hero of the victorious anti-fascist resistance in Barcelona in 1936, as Stalin’s “vassal”? Of course, he was a minister (he resigned in 1937) of the first Popular Front government (Largo Caballero); and his role in May 1937, during the fighting in Barcelona between Stalinists and anarchists (supported by the POUM), negotiating a truce between the two camps, was very questionable. But that does not make him a henchman of the Soviet Bonaparte…

FIARI was founded shortly after the publication of the Manifesto; it succeeded in bringing together not only Trotsky’s supporters and Breton’s friends, but also anarchists and independent writers or artists. The Federation had a publication, the review Clé, whose editor was Maurice Nadeau, at the time a young Trotskyist militant with great interest in surrealism (he became the author, in 1946, of the first Histoire du Surréalisme). The manager was Léo Malet and the National Committee was composed of: Yves Allégret, André Breton, Michel Collinet, Jean Giono, Maurice Heine, Pierre Mabille, Marcel Martinet, André Masson, Henry Poulaille, Gérard Rosenthal, Maurice Wullens. Among the participants we find: Yves Allégret, Gaston Bachelard, André Breton, Jean Giono, Maurice Heine, Georges Henein, Michel Leiris, Pierre Mabille, Roger Martin du Gard, André Masson, Albert Paraz, Henri Pastoureau, Benjamin Péret, Herbert Read, Diego Rivera, Léon Trotsky, … These names give an idea of the capacity of the FIARI to associate quite diverse political, cultural and artistic personalities.

The review Cle only saw 2 issues: n°1 appeared in January 1939 and n°2 in February 1939. The editorial of n°1 was entitled “Pas de patrie!”, And it denounced repression and internment of foreign immigrants by the Daladier government: a very topical issue in 2018!

The FIARI was a beautiful “libertarian Marxist” experience, but of short duration: in September 1939, the beginning of the Second World War put an end, de facto, to the Federation.

Postscript: in 1965, our friend Michel Lequenne, at the time one of the leaders of the PCI, the International Communist Party, French section of the Fourth International, proposed to the Surrealist Group a refoundation of the FIARI. It seems that the idea did not displease André Breton, but it was finally rejected by a collective declaration, dated April 19, 1966 and signed by Philippe Audoin, Vincent Bounoure, André Breton, Gérard Legrand, José Pierre, Jean Schuster – for the Surrealist Movement.

Bibliographic note: the book by Arturo Schwarz, André Breton, Trotsky et anarchy (Paris, 10/18, 1974) contains not only the text of the FIARI Manifesto but also all of Breton’s writings on Trotsky, as well as a substantial historical introduction of 100 pages by the author, who was able to interview Breton himself, Jacqueline Lamba, Van Heijenoort and Pierre Naville. One of the most moving documents in this collection is the speech made by Breton at the funeral in Paris in 1962 for Natalia Sedova Trotsky. After paying homage to this woman whose eyes experienced “the most dramatic battles between shadows and light”, he concluded with this stubborn hope: the day will come when not only justice will be done to Trotsky, but also “to ideas for which he gave his life”.

Courtesy Fourth International