By Michael Roberts

According to AFP estimates, some 1.7 billion people across the world are now living under some form of lockdown as a result of the coronavirus. That’s almost a quarter of the world population. The world economy has seen nothing like this.

Nearly all economic forecasts for global GDP in 2020 are for a contraction of 1-3%, as bad if not worse than in the Great Recession of 2008-9. And forecasts for the major economies for this quarter ending this week and the next quarter are coming in at an annualised drop of anything between 20-50%! The economic activity indicators (called PMIs), which are surveys of company views on what they are doing, are recording all-time lows of contraction for March.

US composite PMI to March 2020

This is all due to the lockdown of businesses globally and isolation of workers in their homes. Could the lockdowns have been avoided so that this drastic ‘supply shock’ would not have been necessary in order to cope with the pandemic? I think it probably could. If governments had acted immediately with the right measures when COVID-19 first appeared, the lockdowns could have been averted.

This is all due to the lockdown of businesses globally and isolation of workers in their homes. Could the lockdowns have been avoided so that this drastic ‘supply shock’ would not have been necessary in order to cope with the pandemic? I think it probably could. If governments had acted immediately with the right measures when COVID-19 first appeared, the lockdowns could have been averted.

What were these right measures? What we now know is that everybody over the age of 70 years and/or with medical conditions should have gone into self-isolation. There should have been mass testing of everybody regularly and anybody infected quarantined for up to two weeks. If this had been done from the beginning, then there would have been fewer deaths, hospitalisations and a quicker dying out of the virus. So lockdowns could probably have been avoided.

What were these right measures? What we now know is that everybody over the age of 70 years and/or with medical conditions should have gone into self-isolation. There should have been mass testing of everybody regularly and anybody infected quarantined for up to two weeks. If this had been done from the beginning, then there would have been fewer deaths, hospitalisations and a quicker dying out of the virus. So lockdowns could probably have been avoided.

But testing and isolation was not done at the beginning in China. At first there was denial and a cover-up of the virus risk. By the time the Chinese authorities acted properly with testing and isolation, Wuhan was inundated and a lockdown had to be applied.

At least the Chinese had the excuse that this was a new virus unknown to humans and its level of infection, spread and mortality was not known before. But there is no excuse for governments in the major capitalist economies. They had time to prepare and act. Italy left it too late to apply testing and isolation so that the lockdown there was closing the doors after the virus had bolted. Their health system is now overloaded and can hardly cope.

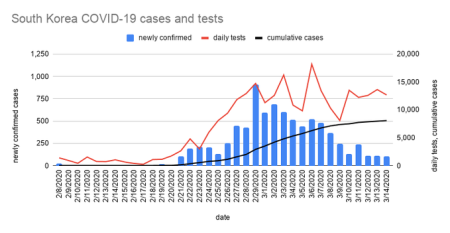

There were some countries that did adopt mass testing and effective isolation. South Korea did both; and Japan where 90% of the population wore masks and gloves and washed, appears to have curbed the impact of the pandemic through effective self-isolation without having a lockdown.

Similarly, in one small Italian village amid the pandemic, Vo Euganeo, which actually had Italy’s first virus death, they tested all 3000 residents and quarantined the 3% affected, even though most had no symptoms. Through isolation and quarantine, the lockdown there lasted only two weeks.

At the other extreme, the UK and the US have taken ages to ramp up testing (which is still inadequate) and get the vulnerable to self-isolate. In the US, the federal government is still not going for a state-wide lockdown.

Why did the G7 governments and others fail to act? As Mike Davis explains, the first and foremost reason was that the health systems of the major economies were in no position to act. Over the last 30 years, public health systems in Europe have been decimated and privatised. In the US, the dominant private sector has slashed services in order to boost profits. According to the American Hospital Association, the number of in-patient hospital beds declined by an extraordinary 39% between 1981 and 1999. The purpose was to raise profits by increasing ‘census’ (the number of occupied beds). But management’s goal of 90% occupancy meant that hospitals no longer had the capacity to absorb patient influx during epidemics and medical emergencies.

Why did the G7 governments and others fail to act? As Mike Davis explains, the first and foremost reason was that the health systems of the major economies were in no position to act. Over the last 30 years, public health systems in Europe have been decimated and privatised. In the US, the dominant private sector has slashed services in order to boost profits. According to the American Hospital Association, the number of in-patient hospital beds declined by an extraordinary 39% between 1981 and 1999. The purpose was to raise profits by increasing ‘census’ (the number of occupied beds). But management’s goal of 90% occupancy meant that hospitals no longer had the capacity to absorb patient influx during epidemics and medical emergencies.

As a result, there are only 45,000 ICU beds available to deal with the projected flood of serious and critical corona cases. (By comparison, South Koreans have more than three times more beds available per thousand people than Americans.) According to an investigation by USA Today “only eight states would have enough hospital beds to treat the 1 million Americans 60 and over who could become ill with COVID-19.”

Local and state health departments have 25% less staff today than they did before Black Monday 12 years ago. Over the last decade, moreover, the CDC’s budget has fallen 10% in real terms. Under Trump, the fiscal shortfalls have only been exacerbated. The New York Times recently reported that “21 percent of local health departments reported reductions in budgets for the 2017 fiscal year.” Trump also closed the White House pandemic office, a directorate established by Obama after the 2014 Ebola outbreak to ensure a rapid and well-coordinated national response to new epidemics.

The for-profit nursing home industry, which warehouses 1.5 million elderly Americans, is highly competitive and is based on low wages, understaffing and illegal cost-cutting. Tens of thousands die every year from long-term care facilities’ neglect of basic infection control procedures and from governments’ failure to hold management accountable for what can only be described as deliberate manslaughter. Many of these homes find it cheaper to pay fines for sanitary violations than to hire additional staff and provide them with proper training.

The Life Care Center, a nursing home in the Seattle suburb of Kirkland, is “one of the worst staffed in the state” and the entire Washington nursing home system “as the most underfunded in the country—an absurd oasis of austere suffering in a sea of tech money.” (Union organiser). Public health officials overlooked the crucial factor that explains the rapid transmission of the disease from Life Care Center to nine other nearby nursing homes: “Nursing home workers in the priciest rental market in America universally work multiple jobs, usually at multiple nursing homes.” Authorities failed to find out the names and locations of these second jobs and thus lost all control over the spread of COVID-19.

Then there is big pharma. Big pharma does little research and development of new antibiotics and antivirals. Of the 18 largest US pharmaceutical companies, 15 have totally abandoned the field. Heart medicines, addictive tranquilizers and treatments for male impotence are profit leaders, not the defences against hospital infections, emergent diseases and traditional tropical killers. A universal vaccine for influenza—that is to say, a vaccine that targets the immutable parts of the virus’s surface proteins—has been a possibility for decades, but never deemed profitable enough to be a priority.

I have argued in previous posts that COVID-19 was not a bolt of the blue. Such pandemics have been forecast well in advance by epideomologists, but nothing was done because it costs money. Now it’s going to cost a lot more.

The global slump is here. But how long and how deep will it be? Most forecasts talk about a short, sharp drop followed by a quick recovery. Will that happen? It depends on how quickly the pandemic can be controlled and fade away – at least for this year. On 8 April, the lockdown in Wuhan will be lifted as there are no new cases. So, from the emergence of virus there in January, it will be about three months, with a lockdown of over two months. It also seems that the peak of the pandemic may have been reached in Italy which has been in full lockdown for only two weeks. So perhaps in another month or two, Italy will be freed. But other countries like the UK are just entering a lockdown phase, with others still facing exponential growth in cases which may require lockdowns.

So it seems that an end to the global supply shock is unlikely before June, probably much later. Of course, the production collapse could be reversed earlier if governments decide not to have lockdowns or to end them early. The Trump administration is already hinting at lifting any lockdown in the next 15 days ‘to get the economy going’ (at the expense of more deaths etc); but many state governors may not go along with that.

Even if economies do bounce back in the second half of 2020 as the lockdowns are ended, there will still be a global slump. And it is a vain hope that recovery will be quick and sharp in the second half of this year. There are two reasons to doubt that. First, the global economy was already slipping into recession before the pandemic hit. Japan was in recession; The Eurozone was close to it and even US growth had slowed to under 2% a year.

And many large so-called emerging economies like Mexico, Argentina and South Africa were already contracting. Indeed, capital was flooding out of the global south to the north, a process than has now accelerated with the pandemic to record levels. With the collapse in energy and industrial metal prices, many commodity-based emerging economies (Brazil, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Ecuador etc) face a huge drop in export revenues. And this time, unlike 2008, China will not quickly return to its old levels of investment, production and trade (especially as the trade war tariffs with the US remain in place). For the whole year, China’s real GDP growth could be as low as 2%, compared to over 6% last year.

With the collapse in energy and industrial metal prices, many commodity-based emerging economies (Brazil, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Ecuador etc) face a huge drop in export revenues. And this time, unlike 2008, China will not quickly return to its old levels of investment, production and trade (especially as the trade war tariffs with the US remain in place). For the whole year, China’s real GDP growth could be as low as 2%, compared to over 6% last year.

Second, stock markets are jumping back because of the recent Fed credit injections and the expected huge US Congress fiscal measures. But this slump will not be avoided by central bank largesse or the fiscal packages being planned. Once a slump gets under way, incomes collapse and unemployment rises fast. That has a cascade or multiplier effect through the economy, particularly for non-financial companies in the capitalist sector. This will lead to a sequence of bankruptcies and closures.

And corporate balance sheets are dangerously frail. Across the major economies, concerns have been rising over mounting corporate debt. In the United States, against the backdrop of decades-long access to cheap money, non-financial corporations have seen their debt burdens more than double from $3.2 trillion in 2007 to $6.6 trillion in 2019.

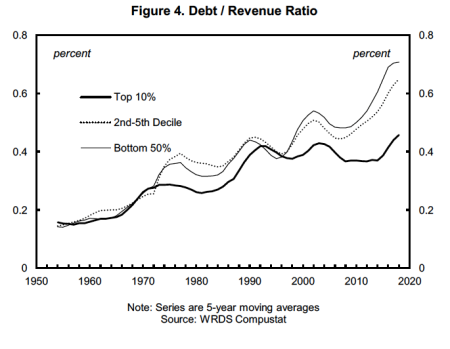

A recent paper by Joseph Baines and Sandy Brian Hager starkly reveals all. For decades, the capitalist sector has switched from investing in productive assets and moved to investing in financial assets – or ‘fictitious capital’ as Marx called it. Stock buybacks and dividend payments to shareholders have been the order of the day rather than re-investing profits into new technology to boost labour productivity. This particularly applied to larger US companies.

As a mirror, large companies have reduced capital expenditure as a share of revenues since the 1980s. Interestingly, smaller companies engaged less in ‘financial engineering’ and continued to raise their investment. But remember the bulk of investment comes from the large companies.

As a mirror, large companies have reduced capital expenditure as a share of revenues since the 1980s. Interestingly, smaller companies engaged less in ‘financial engineering’ and continued to raise their investment. But remember the bulk of investment comes from the large companies.

The vast swathe of small US firms is in trouble. For them, profit margins have been falling. As a result, the overall profitability of US capital has fallen, particularly since the late 1990s. Baines and Hager argue that “the dynamics of shareholder capitalism have pushed the firms in the lower echelons of the US corporate hierarchy into a state of financial distress.” As a result, corporate debt has risen, not only in absolute dollar terms, but also relative to revenue, particularly for the smaller companies.

The vast swathe of small US firms is in trouble. For them, profit margins have been falling. As a result, the overall profitability of US capital has fallen, particularly since the late 1990s. Baines and Hager argue that “the dynamics of shareholder capitalism have pushed the firms in the lower echelons of the US corporate hierarchy into a state of financial distress.” As a result, corporate debt has risen, not only in absolute dollar terms, but also relative to revenue, particularly for the smaller companies.

Everything has been held together because the interest on corporate debt has fallen significantly, keeping debt servicing costs down. Even so, the smaller companies are paying out interest at a much higher level than the large companies. Since the 1990s, their debt servicing costs have been more or less steady, but are nearly twice as high as for the top ten percent.

Everything has been held together because the interest on corporate debt has fallen significantly, keeping debt servicing costs down. Even so, the smaller companies are paying out interest at a much higher level than the large companies. Since the 1990s, their debt servicing costs have been more or less steady, but are nearly twice as high as for the top ten percent.

But the days of cheap credit could be over, despite the Fed’s desperate attempt to keep borrowing costs down. Corporate debt yields have rocketed during this pandemic crisis. A wave of debt defaults is now on the agenda. That could “send shockwaves through already-jittery financial markets, providing a catalyst for a wider meltdown.”

But the days of cheap credit could be over, despite the Fed’s desperate attempt to keep borrowing costs down. Corporate debt yields have rocketed during this pandemic crisis. A wave of debt defaults is now on the agenda. That could “send shockwaves through already-jittery financial markets, providing a catalyst for a wider meltdown.”

Even if the lockdowns last only a few months through to the summer, that contraction could see hundreds of small firms go under and even some big fish too. The idea that the major economies can have a V-shaped recovery seems much less likely than a L-shaped one.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Blog