By Edgar López Rosales

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the students’ massacre on October 2, 1968, in Tlatelolco, Mexico City. It was perpetrated by the Mexican army and by paramilitary groups linked to the Presidential General Staff. It is a crime by the Mexican state which has gone unpunished, even though in recent years evidence has emerged of the responsibility of the then President, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and a top politician (later also President) Luis Echeverría.

Official data of the students’ deaths are not reliable, but according to the latest declassified documents of the US Embassy in Mexico, between 150 and 200 people died in the massacre on October 2, 1968.

The Revolutionary Atmosphere on 1968

The events of that October in Mexico were not isolated from the rest of the world. At that time, the youth had re-entered the political scene, remembering events such as those France in May and the Prague Spring as well as the opposition to the Vietnam War. There was a great deal of support among Mexican youth also for the Cuban revolution.

Capitalism was at the point of its greatest economic upswing in history, as a consequence of the recovery after the destruction of the Second World War. However, minimal democratic freedoms were denied in many parts of the world, including in Mexico.

During that time the country was experiencing strong economic growth, what capitalist academics and economists like to call “the Mexican miracle.” However, this economic growth was not due to government policies, but as a consequence of the particularities of Mexican capitalism of that time, which relied on state intervention.

Because of the Mexican Revolution, some democratic and economic advances were achieved, although the revolution ended up being usurped by a bureaucracy which kidnapped the revolution and gained power, mixing with the Porfirian “aristocrats” (named after the leading Mexican general who was President seven times, before and after the revolution) who had been defeated but not exterminated. This created a new capitalist class and politically represented by a single political party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI in Spanish).

The PRI was formed as a totalitarian and corporate party that controlled all government agencies, trade unions, social organizations and all economic, cultural and social activity in the country. The party did not allow dissidence and any opposition was quickly repressed at the cost even of the lives of the dissidents. The PRI did not represent the revolutionary aspirations of the people, but precisely the contrary, it coerced them and turned the working masses into faithful servants of the party, the State and the capitalist class (in that order).

1968 and International Movements

However, by the end of the 1950s, the first movements of resistance in the workers and peasants movement began to manifest themselves. Standing out were the struggle of the railroad workers and doctors, who were brutally repressed and their leaders imprisoned in the prison of the Lecumberri, which became the main prison for political prisoners at that time. This situation was constant throughout the 1960s until the student movement of 1968 developed.

The student movement consists mainly of young people from the two main universities in the country, the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN). Inside the student movement, all the class contradictions that exist in society are reflected. At that time the workers’ and peasants’ movement was strongly repressed, and its leaders imprisoned, so the social discontent took another way of expression, through the student movement. This also reflected the changes and aspirations of the middle class as social and economic benefits were denied to most of the population.

Although the student movement was made up of many young people of the working class and peasant backgrounds and was influenced by communist ideas, the movement did not go beyond a program of democratic demands. However, for the authoritarian government, even this was intolerable.

The Events in Mexico

On July 22, a fight between students of an IPN high school and an UNAM high school ended up being infiltrated by porros (gang members) from each school. Porros incited violence and attacked police officers and those responded with excessive violence. The police officers entered vocacional #2 (an IPN high school), hit students and destroyed furniture.

On July 26, a protest march against police brutality was called, this march coinciding with the commemorative march for the Cuban Revolution. This ended up as a joint march, aiming for the zócalo (central park of Mexico City). However, they were detained by cops, who did not allow them to reach the zócalo, causing a confrontation between students and police, with several wounded and detained. Arbitrary arrests of students and members of the communist youth continue days after this confrontation.

By July 30, the army intervened by destroying the door of high school #1 with a bazooka. From this moment the student organization took off in schools like IPN, UNAM, Chapingo and Normal de Maestros. On August 2, a National Strike Council (CNH) was formed, and this became the highest decision-making and organizational body of the student movement.

On August 4, the CNH presented a list of six demands:

1. The release of political prisoners

2. Repeal of those articles of the Federal Criminal Code which served to justify the aggression against students

3. Removal of the Grenadier Corps

4. Dismissal of the police chiefs of Mexico City

5. Compensation to the relatives of all the dead and wounded since the beginning of the conflict

6. Demarcation of responsibilities of officials who participate in violent acts.

On August 27, a march to the zocalo was organised to present for the petition, and thousands of students stayed on in the Zocalo to wait for the answers to their demands. However, they were evicted at dawn by army tanks, soldiers and grenadiers. The students were persecuted and arrested throughout the historic centre of Mexico City by state security forces.

On August 27, a march to the zocalo was organised to present for the petition, and thousands of students stayed on in the Zocalo to wait for the answers to their demands. However, they were evicted at dawn by army tanks, soldiers and grenadiers. The students were persecuted and arrested throughout the historic centre of Mexico City by state security forces.

On September 7, a “march of silence” was summoned, where the students marched in complete silence, covering their mouths and without issuing slogans. On September 18, the army invaded the University campus of UNAM, taking students by surprise. On September 23, the army sought to take the IPN, but the students, already prepared, resisted all morning until they were finally, beaten by the army, with hundreds of students arrested.

Mexico City Olympic Games

On October 1, the army left UNAM and IPN. On 2nd of October, the movement tried to reorganize by calling a rally in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco. During the rally, a flare was thrown by a helicopter, thus giving the signal for a paramilitary group of the government (“The Olympia Battalion”), to start shooting at the crowd. This shooting was used to “justify” the intervention of the army and that afternoon more than 150 students were killed in the Plaza. Dozens more were injured and many were arrested and taken to military camps. The objective of the government was to crush the movement, 10 days before the start of the Olympic Games of Mexico.

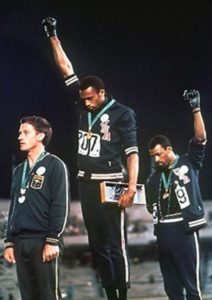

The “Black Power Salute” was a political demonstration conducted by African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos during their medal ceremony on October 16, 1968, in the Olympic Stadium, Mexico City.

After the brutal repression, those who were responsible not only went unpunished but remained firmly in government. Luis Echeverría, who was government secretary and one of the main leaders, assumed the presidency in 1970. By June 10, 1971, the student movement tried to reorganize but was again repressed by the paramilitary group known as the “Hawks”.

The decade of the 1970s became one of the darkest periods in the history of the country, where repression, arrests and executions became a daily fact of life. The genocide perpetrated by the government on the afternoon of October 2, 1968, has remained a painful and bloody memory for the country. Fifty years later, this genocide still goes unpunished.

In 2005, a judge exonerated Luis Echeverría and claimed he could not find evidence for the crime of genocide. But it has always been evident that protection was provided from the PRI governments and the National Action Party (PAN, conservative) for Echeverría, who was always an executor of the policies of the capitalist class and the US governments. Echeverria presented himself as a Latin America leader, but in fact, he fought against left-wing and revolutionaries governments such as those of Fidel Castro in Cuba and Allende in Chile. Moreover, according to declassified information from the United States government, it would be known much later that both Echeverría and Díaz Ordaz were US agents, paid by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), as part of operation “LITEMPO” the Latin American anti-communist struggle of the United States government.

In 2000, after 70 years governed by the PRI party, for the first time the National Action Party (PAN) won the presidential elections. However, the new ruling party was not interested in doing justice for all the crimes previously committed. The PAN, another right-wing party is closely linked to sectors of the big capitalist class and the PR and it repudiates social movements, using similar methods of repression as in the case of Atenco and Oaxaca in 2006.

This year, with the arrival of a ‘leftist’ presidency, for the first time in decades, there opens up a small hope that justice can be done for all the massacres and repressions committed by previous governments. There can be no peace in Mexico if there is no justice. The new government cannot act as a puppet of criminals and murderers. Today more than ever, fifty years after, the student massacre in Tlatelolco is not forgotten.