By Michael Roberts

‘Get Brexit Done!’ that was the campaign slogan of the incumbent Conservative government under PM Boris Johnson. And it was the message that won over a sufficient number of those Labour voters who had voted to leave the EU in 2016 to back the Conservatives. One-third of Labour voters in the 2017 election wanted to leave the EU, mainly in the midlands and north of England, and in the small towns and communities that have few immigrants. They have accepted the claim that their poorer living conditions and public services were due to the EU, immigration and the ‘elite’ of the London and the south.

Britain is the most divided in Europe geographically. The election confirmed this ‘geography of discontent’, where rates of mortality vary more within Britain than in the majority of developed nations. The disposable income divide is larger than any comparable country and has increased over the past 10 years. The productivity divide is also larger than any comparable country.

The ‘leave’ view was stronger among those who are old enough to imagine the ‘good old days’ of English ‘supremacy’ when ‘we were in control’ before joining the EU in the 1970s. Once in the EU, we had the volatile 1970s and the crushing of manufacturing and industrial communities in the 1980s. The flood of Eastern European immigrants (actually mainly to the large cities) in the 2000s was the last straw.

In the ’remain capital’ of England, London, Labour’s vote held up as the ‘remain’ party, the Liberal Democrats, were squeezed down. The LDs did badly but still had a higher share of the vote (11%) than in 2017. The Conservative share of the vote rose only slightly from 2017 (42.3% to 43.6%), but Labour’s slumped from 40% in 2017 to 32%. So the opinion polls and the exit polls were very accurate. Indeed, the overall turnout was down from 69% in 2017 to 67%, particularly in the Brexit areas. Once again, the ‘no vote party’ was the largest.

This was clearly a Brexit election. The Labour party had the most radical left-wing programme since 1945. The social and economic manifesto of the left Labour leadership was actually quite popular. Labour’s campaign was excellent and the activist turnout to canvass and get the vote in was terrific. But in the end it made little difference. Brexit still dominated and the Labour vote was squeezed. Not every voter wanted to ‘get Brexit done’, but clearly sufficient of the 2016 ‘leave’ voters had enough of delay and procrastination by former PM May and parliament and wanted the issue dealt with.

Usually, elections are won on what the state of the economy is. This election was generally different. But even so, the measure of ‘economic well-being’ index (based on a mix of the change in real disposable income and unemployment rate) suggested an improvement since former PM May lost her majority in 2017. The economy at the level of investment and output may have been stagnating, but the average UK household was feeling slightly better off since 2017, with full employment and slight improvement in real incomes. That helped the Johnson government.

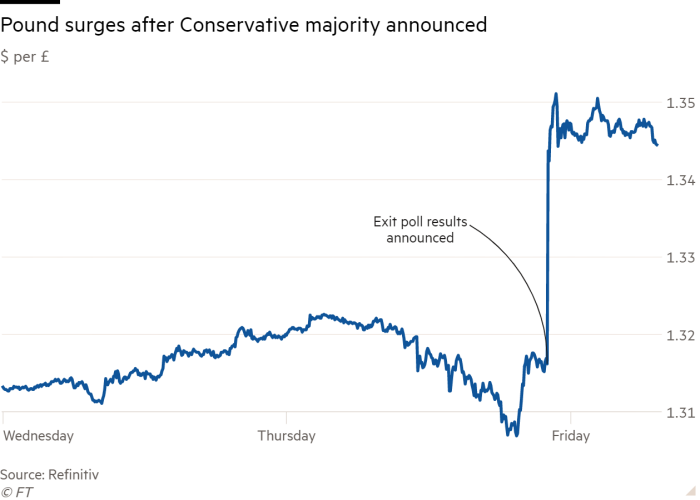

What now? The government under Johnson will now move quickly to pass through parliament the legislation necessary for the UK to leave the EU by end of January at the latest. And then the more tortuous process of signing up a trade deal with the EU will begin. That is supposed to be completed by June 2020, unless the UK asks for an extension. Johnson will try to avoid that and he can now make all kinds of concessions to the EU in order to get a deal done without the fear of a backlash from ‘no deal’ Brexiters in his party, as he has a big enough majority to see them off.

With the Brexit issue likely to be out of the way by this time next year, the British economy, which has been on its knees (stagnation of GDP and investment) is likely to have a short pick-up. With ‘uncertainty’ over, foreign investment may return, house prices recover and with the labour market tightening, wages may even pick up. The Johnson government may even steal some of Labour’s proposals and boost public spending for a short period.

Longer term, the future of the British economy is dismal. All studies show that outside the EU, the British economy will grow slower in real terms than it would have done if it had remained an EU member. The degree of relative loss is estimated at between 4-10% of GDP over the next ten years, depending on the terms of the trade and labour deal with the EU. Also, it is still unclear how much damage there will be to the financial services sector in the City of London. But this is all relative; implying just 0.4-1% off the projected annual growth rate. So, for example, if the UK grew at 2% a year in the EU, it would now grow at about 1.5% a year.

And then there is the joker in the pack: the global economy. The major capitalist economies are growing at the slowest rate since the Great Recession. There may be a temporary truce in the ongoing trade war between the US and China, but it will break out again. And corporate profitability in the US, Europe and Japan is sliding, alongside rising corporate debt. The risk of a new world economic recession is at its highest since 2008. If a new global slump comes, then the mood of the British electorate may change sharply; and the Johnson government’s Brexit bubble will then be pricked.

Courtesy Michael Roberts Bolg