By Roger Silverman

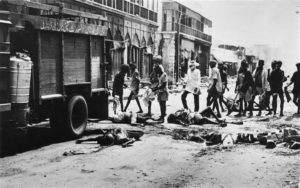

THE END of the Second World War inspired a global movement towards revolution, particularly in the colonies of the “victorious” imperial powers of Britain and France. The uprising that swept the Indian sub-continent in 1945-6 was a united mass movement mobilising millions of working people, democratic and secular, cutting across all cultural, ethnic, and communal barriers. It ended in British withdrawal, but the victory was tragically stained with the blood of communal massacres and partition.

This article, first published in 1985, explodes the myths that have surrounded the winning of India’s independence. In the three decades since it was written, the grip of the global corporations has further tightened around the economies of both India and Pakistan, and the secular pretensions of both sides are long since abandoned as their hostile nuclear-equipped armies face each other.

*************************************

THE DECAY of capitalism has plunged humanity into the most unstable epoch of its history. It is hardly surprising then that the most populous country of capitalism, in which its failure to develop society is most spectacular—India—is also at present probably the most volatile in the world. The last one year has witnessed enough cataclysms to last a “normal” society decades: communal and caste massacres, coups, general strikes, assassinations, mutinies, untold social upheavals in every state.

THE DECAY of capitalism has plunged humanity into the most unstable epoch of its history. It is hardly surprising then that the most populous country of capitalism, in which its failure to develop society is most spectacular—India—is also at present probably the most volatile in the world. The last one year has witnessed enough cataclysms to last a “normal” society decades: communal and caste massacres, coups, general strikes, assassinations, mutinies, untold social upheavals in every state.

The prospect opens up of the very disintegration of India, after four decades of independence. In particular, the Punjab crisis could start a chain reaction leading to the creation of a dozen statelets, each with its own national questions. What would be left would be, not a “Greater India”, but a Lesser Hindustan, encompassing the poorest and most wretched Northern states of the “Hindi belt”, a Hindu theocratic state in which Muslims, Sikhs and other religious minorities would be plunged into an inferno of pogroms, counter-terror and repression. If capitalism is not overthrown, India will explode into bleeding fragments. If the workers and peasants take power and thus avert this catastrophe, it will be in unity with those of the neighbouring countries, to create the Socialist United States of the Indian Sub-Continent.

These tortured convulsions are a direct result of the failure of the bourgeoisie to solve a single one of its tasks. The theory of Permanent Revolution explains that in the modern epoch the bourgeoisie in the underdeveloped countries is incapable of repeating the pioneering and revolutionary role played at the dawn of capitalism by the bourgeoisie of the West: that the tasks of the bourgeois-democratic revolution, national unification, industrialisation, division of the landed estates, etc… can only be solved along with the tasks of the socialist revolution: nationalisation of the means of production, state monopoly of foreign trade, etc.

The emergence of a national consciousness, the vision of a united, secular, democratic Indian nation, was one of the products of the elemental movement for national liberation that was to transform the face of the planet. Some have misunderstood the fact that Congress assumed power in 1947 as a refutation of the Permanent Revolution, or at least as a sign that the Indian bourgeoisie was in some way an exception: that it was fit at least to begin tackling the tasks of establishing a modern capitalist nation. But the Indian bourgeoisie never led a national-liberation struggle. Congress did not win the power; it dropped into its lap due to the exhaustion and senility of imperialism, amid the revolutionary ferment that gripped the world following the end of the world war.

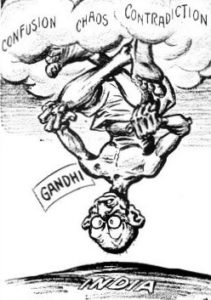

Gandhi’s Role

The mantle of revolutionary democrats lies especially uneasily on the shoulders of Congress. As befitted a weak and dependent bourgeoisie, its whimpering plea for greater political responsibilities was slavish and cowardly and it huddled with imperialism at every turn in fear of the masses. The crafty lawyer Gandhi with his messianic delusions went a little further than his urbane colleagues in transcending the cramped barriers of local particularism, caste, superstition, and communal bigotry, an indispensable condition if concessions were to be wrested from imperialism. But at all costs the downtrodden hordes must be kept in a subordinate and passive role: they must be pacified, hence quite literally the “pacifism” of Congress—which once in power proved to be among the most bloodthirsty of capitalist regimes in repressing the workers and peasants. The Indian National Congress was paralysed from the beginning by fear of the masses and squirmed a tortuous middle path between the needs of imperialism, to which it swore loyalty, and the aspirations of the masses for freedom, in the interests of levering a more favourable bargaining position for itself. It devised the tactics of “non-violence”—the hunger strike, civil disobedience and passive resistance—as a means of syphoning off the fury of the masses while exploiting them as a bargaining counter.

The mantle of revolutionary democrats lies especially uneasily on the shoulders of Congress. As befitted a weak and dependent bourgeoisie, its whimpering plea for greater political responsibilities was slavish and cowardly and it huddled with imperialism at every turn in fear of the masses. The crafty lawyer Gandhi with his messianic delusions went a little further than his urbane colleagues in transcending the cramped barriers of local particularism, caste, superstition, and communal bigotry, an indispensable condition if concessions were to be wrested from imperialism. But at all costs the downtrodden hordes must be kept in a subordinate and passive role: they must be pacified, hence quite literally the “pacifism” of Congress—which once in power proved to be among the most bloodthirsty of capitalist regimes in repressing the workers and peasants. The Indian National Congress was paralysed from the beginning by fear of the masses and squirmed a tortuous middle path between the needs of imperialism, to which it swore loyalty, and the aspirations of the masses for freedom, in the interests of levering a more favourable bargaining position for itself. It devised the tactics of “non-violence”—the hunger strike, civil disobedience and passive resistance—as a means of syphoning off the fury of the masses while exploiting them as a bargaining counter.

Churchill mocked the “naked fakir” Gandhi, but the obese, rapacious and parasitical Indian bourgeoisie needed as its mascot the caricatured saint with his sackcloth, his fasting and his pacifism. The writings of Gandhi, once the prisoner of the British imperialists and now their darling, express with breath-taking frankness the striving of the Indian bourgeoisie to subdue the storm of mass revolt.

“I think the growing generation will not be satisfied with petitions, etc…” he advised. “We must give them something effective. Satyagraha (passive resistance) is the only way, it seems to me, to stop terrorism” (i.e. direct action including mass uprisings). Gandhi’s first priority was to safeguard the rights of private property. He expressed horror at finding in his native state of Gujarat “utter lawlessness bordering on Bolshevism”.

“I shall be no party to dispossessing the propertied classes of their private property without just cause,” he assured the landlords and capitalists. “You may be sure that I shall throw the whole weight of my influence in preventing a class war. Supposing there is an attempt unjustly to deprive you of your property, you will find me fighting on your side.”

He understood all too clearly that once the masses were on the move, the struggle would inevitably go far beyond the formal political goal of independence, to sweep capitalism and landlordism aside: “I hope I am not expected knowingly to undertake a fight that must end in anarchy and red ruin”, he replied to the suggestion of a general strike. He consciously used the “socialist” wing of Congress to confuse them: “It is all well as long as you hold the peasants in check. But Nehru’s presence must now ease the situation. He has no difficulty in dealing with the peasants and restraining them.”

There were strict limits to his advocacy even of civil disobedience. “I cannot ask officials and soldiers to disobey,” he explained frankly (and prophetically), “for when I am in power I shall in all likelihood make use of these same officials and those same soldiers. If I taught them to disobey I shall be afraid that they might do the same when I am in power.” Gandhi’s servile posture towards the British Raj can be indicated, quite apart from his frequent and toadying protestations of loyalty and “love” for the British Empire, by the fact that two entire volumes of his collected works are devoted to his correspondence with the Viceroy! One or two extracts will be as much as our readers will be able to stomach…“It would be unwise on my part not to listen to the warning given by the Government… A civil resister never seeks to embarrass the Government. I feel that I shall better serve the country and the Government by the suspension of civil resistance for the time being.” And again: “I confess that it is a delicate situation. I need hardly assure you that the whole of my weight will be thrown absolutely on the side of preserving internal peace. The Viceroy has the right to rely upon my doing nothing less.”

Dismayed that the dialectic of events had prompted a breach in relations, Gandhi did not hesitate to crawl back into favour by writing to the Viceroy: “I do not know whether… friendly relations between us are closed, or whether you expect me still to see you and receive guidance from you as to the course I am to pursue in advising the Congress.”

“I wish I could convince all the British public men, the British Ministers”, he complained, “that Congress is capable of delivering the goods.”

Trotsky summed up the delicate and complex task that faced the Indian bourgeoisie:

“Millions of people have begun to stir. They demonstrated such spontaneous power that the national bourgeoisie was forced into action in order to blunt its revolutionary edge. Gandhi’s passive resistance movement is the tactical knot that ties the naiveté and self-denying blindness of the dispersed petty- bourgeois masses to the treacherous manoeuvres of the liberal bourgeoisie… The Tolstoyan formulas of passive resistance were in a sense the first stage of the revolutionary awakening of the Russian peasant masses. Gandhism represents the same thing in regard to the masses of the Indian people. The more ‘sincere’ Gandhi is personally, the more useful he is to the masters as an instrument for the disciplining of the masses.” (The Revolution in India, its Tasks and Dangers, 1930) “We denounce before the colonial masses the treacherous aspects of Gandhism, whose mission is to retard the fight of the revolutionary masses and to exploit it in the interest of the `national’ bourgeoisie.” (1934).

The natural leadership of the independence struggle belonged to the party of the proletariat. But the Communist Party of India displayed an even greater degree of treachery than Congress.

“Communist Collaboration”

It was a historical betrayal by world Stalinism that led the CPI in 1942 to denounce as treason the massive ‘Quit India’ campaign half-heartedly launched by Congress, which had an ambiguous and inconsistent attitude to the war. In accordance with its role as a puppet of the Kremlin bureaucracy and frontier-guard of the USSR, rather than the vanguard of the workers and peasants or even of the national-liberation movement, the CPI put Stalin’s alliance with Churchill before the cause of India’s freedom. The only sure defence of the Russian revolution was to advance the struggle against imperialism everywhere.

But CPI leaders entered into a prolonged and increasingly servile secret correspondence and even held secret meetings with the British authorities, volunteering their collaboration in fighting against the Congress “fifth column”. In April 1942 the CPI submitted a memorandum to the government declaring: “Today all the Indian Communists are burning with an ardent desire to co-operate with the existing war efforts, even under the present government”, and requesting official help to “enable us to resist the Japs…We have no doubt that the government will find our organ the most effective war propaganda newspaper that has yet been introduced in India.” The party offered “our wholehearted cooperation” in sending its released leaders on countrywide tours “to rouse the patriotic instincts of the people in defence of our country”, “undertake recruitment for all branches of the fighting forces”, “do all we can to build fraternal relations between the army and the people”, “work out schemes for speeding up production”, etc. The government “will have no need to fear strikes as far as we Communists can help it”.

The party continually bragged about its successes at breaking strikes, preventing food riots and discouraging desertions, gloating that even the pro-imperialist newspapers “have not written so consistently and strongly against sabotage as our weekly organs”.

British bureaucrats overcame official scepticism with cynical arguments: “When your house is on fire, the important thing is that someone is helping you put it out, not what he was doing previously, It is easy to give a dog a bad name and hang him. It is more difficult, but far more worthwhile, to recognise and seize the moment at which it may be possible to convert a rebel into a useful citizen. The change is in tactics only, but if they change their tactics, their ideology does not matter. We can accept these people as short-term allies, The Communists might provide something of a makeweight against the pernicious activities of Congress”.

As a result, while Congress leaders were imprisoned between 1942 and 1945, and an estimated 10,000 youth, workers and peasants were killed fighting British imperialism and tens of thousands jailed or flogged, the CPI was legalised, its activists freed from the jails, and its newspapers subsidised by the British government! Such was the anger of the masses at this sickening treachery that CPI offices and print shops were bombed and CPI activists attacked. It took years for the CPI to recover any credibility and to this day Congress leaders demagogically exploit this criminal record at election hustings, etc.

The masses showed an unrelenting and growing determination to achieve freedom. Trotsky warned that under such a leadership their efforts were doomed. “The Indian bourgeoisie is incapable of leading a revolutionary struggle. They are closely bound up with and dependent on British capitalism. They tremble for their own property. They stand in fear of the masses. They seek compromises with British imperialism no matter what the price, and lull the Indian masses with hopes of reforms from above. The leader and prophet of this bourgeoisie is Gandhi. A fake leader and a false prophet… Double chains of slavery—that will be the inevitable consequence of the war if the masses of India follow the politics of Gandhi, the Stalinists and their friends.” (India; Faced with Imperialist War, 1939). It was inconceivable that an effete, snivelling party like Congress could wrest the power from the hands of imperialism. How then did the party of the “fake leader and false prophet” come to inherit the power?

The winning of Indian independence was due neither to the saintliness of Gandhi nor the benevolence of Mountbatten, but to the revolutionary wave that rocked the planet following the Second World War, a wave that also launched the global movement towards colonial revolution, swept to power workers’ parties or Popular Fronts in Western Europe, and brought an end to landlordism and capitalism in China and a number of countries in Eastern Europe. In India, the masses tore control of the national liberation struggle out of the quavering hands of Congress.

Revolution

What was the attitude to this magnificent movement of the Congress so-called “leaders” of the independence campaign? One of consternation, Sardar Patel successfully urged the Bombay naval ratings to surrender, promising to use his influence to avoid victimisation — following which they were jailed. Gandhi and Nehru denounced the strikes, and Congress President Maulana Azad said, “Strikes, hartals and defiance of temporary authority are out of place.”

India was ablaze with strikes, mutinies, and uprisings. The Empire was without an Army. Lord Mountbatten was rushed out to organise a hurried withdrawal from India, working in the classic ‘divide and rule’ method of imperialism. Partitioning the living body of the country by giving power to Congress in India and the Muslim League in Pakistan, they thought they would dominate by playing one section against the other. Later he explained: “India in March 1947 was a ship on fire in mid-ocean with ammunition in the hold… It seemed that the only possible alternative to a quick transfer of power was… to bring in a large number of British Army divisions to hold down the country.”

But how many divisions would it need to hold down an angry population of over 500 million? It would take an army of occupation and conquest bigger than the entire British Army to saturate India… And then? In Napoleon’s famous epigram, you can do anything with bayonets except sit on them. And where, in the conditions of that post-war dawn of hope, where the forces for such an army to be found? War-weary, radicalised and determined to go home and build a new world, the British troops were in no mood to play the role of an imperialist occupation army, fighting a dirty war and a lost cause.

If US imperialism had to stand by gritting its teeth while China, the biggest nation on earth, abolished landlordism and capitalism, then how much less could the mangy toothless British lion prevent the political transfer of power to the Indian bourgeoisie? In fact, the radical temper of the British soldiers had already compelled the British Government to demobilise them in haste and take the guns out of their hands. No wonder that General Auchinleck, faced with this forest fire of revolt, cabled back to Whitehall that unless independence were conceded, India could not be held for three days!

In the whole history of British rule, imperialism had never needed a full-scale occupation army in India. Britain conquered India with Indian troops, cunningly intriguing and playing off the rival Maharajahs of the feuding principalities. Even the rebellion of 1857 was localised in character. It took the tidal wave of national consciousness that engulfed India in 1945-7 to sweep the raj away.

Compare the situation in 1853, the heyday of British imperialism, when Marx wrote:

“While all were struggling against all, the Briton rushed in and was enabled to subdue them all… A country not only divided between Mohammedan and Hindu, but between tribe and tribe, between caste and caste, a society whose framework was based on a sort of equilibrium, resulting from a general repulsion and constitutional exclusiveness between all its members. Such a country and such a society, were they not the predestined prey of conquest? If we knew nothing of the past history of Hindustan, would there not be the one great and incontestable fact, that even at this moment India is held in English thraldom by an Indian army maintained at the cost of India?”

India gained its political freedom thanks neither to Congress nor the CPI, but to the revolutionary mood of both the Indian masses and the British troops, and the pressure on the new Labour Government by the British working class. By 1947, the police, army, navy and air force had melted away, and there was no prospect of finding a new occupation army. The cynical right- wing Congress leader Rajagopalachari commented: “If Mountbatten had not transferred power when he did, there might have been no power to transfer.”

Communal Partition

Despite recent attempts to build up a cult of Mountbatten, his role was one not of “brilliant diplomacy” but of rat panic. He negotiated a rapid withdrawal in collusion with the British stooge Jinnah, leader of the Muslim League, which exploited the fears of the Muslim minority of persecution at the hands of a Hindu-dominated Congress government by insisting that Hindus and Muslims constituted “two nations” and demanding partition. British imperialism, with Congress connivance, was responsible for the bloody dismemberment and communal vivisection of India, the slaughter of millions of Hindu and Muslim hostages and the transmigration of tens of millions into refugee camps.

Despite recent attempts to build up a cult of Mountbatten, his role was one not of “brilliant diplomacy” but of rat panic. He negotiated a rapid withdrawal in collusion with the British stooge Jinnah, leader of the Muslim League, which exploited the fears of the Muslim minority of persecution at the hands of a Hindu-dominated Congress government by insisting that Hindus and Muslims constituted “two nations” and demanding partition. British imperialism, with Congress connivance, was responsible for the bloody dismemberment and communal vivisection of India, the slaughter of millions of Hindu and Muslim hostages and the transmigration of tens of millions into refugee camps.

The legacy of British imperialism in India, as in Ireland, the Middle East, Cyprus, etc… was a festering communal poison, which can never be eradicated while capitalism remains. Having done their utmost to damp down the masses’ struggle, the Congress leaders—like their Irish counterparts 25 years previously—meekly accepted communal partition as the price for the trappings of power.

If the bourgeoisie had been capable of playing even the feeblest role in developing society, here was the ideal test of its potential. It could not have dreamed of more favourable conditions. It took hold of the destiny of the most populous capitalist country on Earth, commanding a gigantic potential home market (its population is now as great as those of the USA, the EEC countries and the USSR put together), at the outset of the biggest world economic upswing in the history of capitalism! India is rich in untapped mineral and agricultural reserves, and above all in the most precious and productive resource of all: human labour power. If the Indian bourgeoisie could have arrived on the scene and come to power two or three centuries earlier, India could have been the USA. It’s pitiful condition today proves graphically the historical redundancy of capitalism.

Failure of Capitalism

It is ironic that apologists for capitalism blame India’s poverty on one of the very factors that fuelled the economic “miracles” in Germany, Japan, Italy, Brazil, etc… at the very time that Indian capitalism was hardly hobbling along: “overpopulation”, the availability of surplus manpower, which allowed an influx of fresh reserves of labour into industry in those countries. America’s wealth was founded upon successive waves of immigration, which provided a rare combination of both cheap labour and a booming market. Conversely, the declining populations of Ireland in the 19th century, or India’s neighbour Nepal today, bled by mass emigration, have hardly been beneficial to their economies! Socialism could proudly harness the energies and creative talent of humanity.

The law of permanent revolution has been brilliantly vindicated in reverse by the negative history of Indian capitalism. Not a single task of the bourgeois-democratic revolution has been fulfilled. Capitalism has failed to develop a home market—on the contrary, the already appallingly impoverished masses have been utterly pauperised since independence. The percentage of Indians eking out a brutish existence below starvation level has grown to 60 per cent. This is the material basis for the constant eruptions of rioting, blind despair and communal slaughter in all the cities, and conditions nearing civil war in large areas of the countryside.

Indian capitalism’s unseemly scramble to cash in on foreign booms instead has ended in disaster; with the Indian share of world trade steadily declining throughout the post-war Western boom from its highest point, achieved in 1938! Even in absolute terms, it has now lost its earlier toehold on world markets, and is now, at the insistence of the IMF, demolishing its tariff walls and opening up its limited internal market to a flood of cheap imports threatening the destruction of the bulk of Indian industry. After a feeble flutter, Indian capitalism is now decisively beaten by the monopolies of the West and Japan, which use India as a dumping-ground.

A tiny class of vulgar parvenus has India by the throat, a parasitic bourgeoisie that straddles a shadowy borderline with gangsterism and feeds its gross appetites by sordid speculation, black-marketeering, usury, bribery, smuggling, above all by downright cheating. A huge volume of “black money” is swilling and lurching throughout the economy making a mockery of bureaucratic regulation and “controls”.

If there has been a marginal growth in the industrial proletariat in India since 1947, there is no question that the social class, which has swollen into monstrous proportions during the same period, due to land hunger and unemployment, is the lumpenproletariat of the teeming shantytowns. In terms of land reform, Congress only broke the stranglehold of the feudal landowners in a few areas, notably Punjab (hardly a paragon of stability today!). Landlessness has swollen to half the rural population and five per cent of landlords own 45 per cent of the land.

Congress has failed to wipe out the surviving antiquated and even pre-capitalist forms of production. In fact, there survive primitive communist tribal societies (the `Adivasis’ of Madhya Pradesh, the North-East, etc…) a widespread system of slavery (`bonded labour’ in the stone quarries, plantations, etc….) feudal serfdom, sharecropping and absentee landlordism over the majority of the land; large-scale primitive cottage-industry manufacture; and the economically dominant capitalist monopolies. India thus resembles a huge living museum of historical materialism. This is the clearest token of capitalism’s impotence to decisively put its own imprint on society. Another is the fact that capitalism can only totter along on the crutches of the state; hence two-thirds of labour in the ‘organised sector’ is employed by the state.

Congress has failed to shake off the horrible medieval legacy of the Dark Ages—caste and untouchability, communal bigotry, ignorance and superstition. The economic collapse has led to a resurgence of all that is most vile and barbarous in India’s cultural heritage: communal and caste massacres, witchcraft, astrology, ritual child slaughter, dowry murders, widows’ self-immolation, etc. Rajiv Gandhi boasts of leading India into the 21st century. Most of the country would grateful to be dragged into the 17th century!

Balkanisation

Above all, by betraying the hopes of the independence movement Congress has allowed the flame of national consciousness, which set India alight in 1947 to flicker and dim almost to extinction. This represents its most shameful humiliation, its ultimate historical failure.

The Indian bourgeoisie needs a united India which can provide it both with at least some home market (if in practical terms this amounts to only five per cent of the population, this still means nearly 40 million people) and especially with the lavish public funds of which it milks the state exchequer. The Balkanisation of India would mark its final demise as a class. But it has utterly discredited itself. It can no more hold India together than it can solve any other of its tasks. It has lost all faith in its own future. Thus, just as Indian businessmen will cheat their way around their own laws to make a fast buck out of smuggling and black-money transactions, making a mockery of their own tariff and tax systems, so too their political agents will freely spit upon the sacred cows of Gandhism and nationalism and indulge instead in unscrupulous conspiracies with the dark forces of communal gangsterism for the sake of their personal careers.

Congress has finally, and inevitably, turned a full circle into the party of Northern Hindu communal chauvinism and bigotry. All the more reason, for it to cling desperately to the Nehru/Gandhi family dynasty, a monarchy in all but name, to resuscitate the flagging myth of Congress’ role in 1947. At every time of political crisis when it was faced with a choice—in 1966, 1969-71, 1975, 1979-80, 1982 and again in 1984—it had no alternative but to entrust its fate to succeeding generations of the Nehru family—to his daughter Indira and grandsons Sanjay and Rajiv. History has thus played a cruel joke on Congress. A mass movement for Indian national unity overthrew an Emperor and swept an unwilling Congress into power; one generation later, Congress needs a new Royal dynasty to try in vain to keep India from crumbling to pieces.

The Indian bourgeoisie aped the imperialists by adopting a bullying posture towards the weaker nations of the sub-continent, especially in its national oppression of the Nagas and Mizos in the Northeast, its refusal of a plebiscite in Kashmir, its annexation of Sikkim, etc. It periodically stages local coups by dismissing elected state governments (recently in Kashmir, Sikkim, Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Punjab, etc….) and imposing direct rule. But disillusion and disgust at the antics of the ruling class has soiled the vision of a united India and led to a resurgence of regional and secessionist movements. Most dangerous of all are the complex tensions that have arisen between the overlapping communities, especially within the urban lumpenproletariat, leading to an ugly eruption of communal pogroms against Muslims, Sikhs, etc. But a national consciousness does not drop from the sky; it is founded on a material base. The fragmentation and eclipse of an Indian national consciousness today is rooted in the actual material failure of the bourgeoisie to fulfil its historic mission, and the criminal refusal of the proletarian parties to assume even that responsibility, let alone that of the socialist revolution. The only class that can “save India” is the Indian proletariat, which by its magnificent record of struggle, especially over the last decade, has staked an irrefutable claim to be literally the most militant and combative in the world, and whose proven heroism, tenacity and internationalism testify to the decisive revolutionary role it can play once it finds a worthy political expression.

The decadence of capitalism is nowhere better illustrated than in the countries of the Indian sub-continent. The workers, peasants, youth and unemployed face ever more excruciating agonies in terms of economic hardship and national oppression alike. But Marxists can have no illusions about it: there is no section of the bourgeoisie in any country, rich or poor that can solve these problems. More than ever, the task of historical progress falls on the shoulders of the proletariat with the overthrow of capitalism on a world scale.