By John Pickard

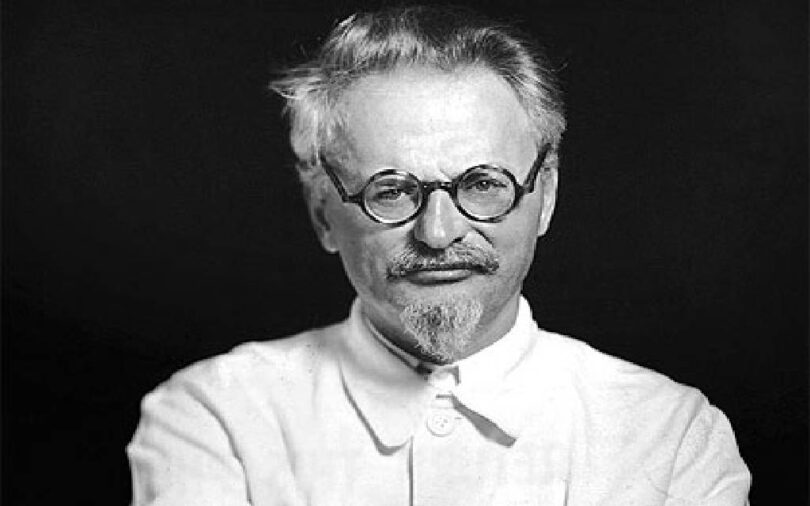

Leon Trotsky’s assassination eighty years ago this week was a vain attempt to suppress the political ideas that he represented, embodying the traditions of genuine Marxism and particularly those of the October Russian Revolution.

His murderer was Ramon Mercader, who had inveigled himself into the circle of acquaintances and secretarial support upon which Trotsky depended in his fortified home in exile in Mexico City. But the real perpetrators of the assassination were Mercader’s paymasters, the Russian Stalinist bureaucracy, which had usurped power for itself in the crisis-laden years after the Revolution and Civil War and in particular after the death of Lenin in 1924.

The Stalinist bureaucracy had excavated a river of blood that separated it from the genuine ideas of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, through the purges and show trials of the 1930s, destroying an entire generation of Bolsheviks. By 1940, of the original leaders of the Bolshevik Party, only Stalin and Trotsky survived, the majority of the rest having met untimely deaths, mostly at Stalin’s hands.

The Russian so-called ‘Communist’ Party had long since abandoned any connection with the Russian Revolution, either politically or in terms of its living members.

Lenin’s Four Conditions

At the time of the Revolution, Lenin had laid down four basic conditions for the maintenance of a workers’ democracy: that all officials be elected and subject to recall, that officials receive no more than the average wage of a skilled worker, that official functions should be regularly rotated to prevent a bureaucracy putting down roots, and that there should be no standing army but an armed people. Within ten years of the Revolution, not one shred of the conditions laid down by Lenin remained.

Trotsky, who with Lenin was co-leader of the Revolution, remained the last Russian of any stature who opposed the monstrous bureaucracy that now ruled the USSR and it was for that reason he was its prime target. Before his death in August, Trotsky had already survived an assassination attempt some weeks earlier.

Had he not been exiled in 1929 – probably the most significant ‘mistake’ Stalin made – he would certainly have died in the purges of the 1930s, alongside the other leaders of the October Revolution. By the time of his own murder, his entire family had been wiped out in the USSR and his son assassinated by agents of Stalin in France. Only his wife and grandson survived with him in Mexico.

For the Stalinist bureaucracy, Trotsky’s ‘crime’ was that he correctly analyzed the social and political origins of the bureaucracy. It was a product, he explained, of the isolation of the Revolution in the most economically-backward country of Europe, moreover, one that was further devastated by the First World War, the Civil War, the armies of intervention from all the major imperialist powers and economic sanctions – all factors producing indescribable hardship and poverty after 1921.

The delay of the revolution in Western Europe and the defeat of the German revolution in particular, further reinforced the isolation of the Revolution and strengthened the hand of a growing bureaucracy that was settling into place under conditions of dire hardship, improvisation and a shortage of all economic necessities.

The Growth of Privilege and Cynicism

The bureaucracy was a layer growing fat on special privileges in conditions of generalised hardship and, wishing to maintain these privileges, it also reflected a cynical pessimism in its political outlook, particularly in regard to world revolution. Thus, what had been viewed as temporary steps backward in terms of inequalities in pay and conditions – as a result of the economic exigencies – became permanently entrenched. The Bolsheviks’ original policy of socialist internationalism became ‘Socialism in One Country’. From being a vehicle to disseminate revolutionary traditions and ideas around the world, the Communist International became a tool of Stalinist foreign policy.

By 1936, Trotsky argued in The Revolution Betrayed, that the political systems (i.e. the government and state) in Stalinist USSR and Nazi Germany were indistinguishable. In both there was an utter lack of democracy, a repressive state apparatus, arbitrary arrests and torture, police spies and prison camps.

The crucially important distinction, Trotsky noted, was that whereas Hitler’s regime rested on the economic foundations of capitalism (albeit with many capitalists discomforted by the looting of the Nazis), the Stalinist bureaucracy drew its power from a state-owned and planned economy. While he therefore continued to raise the banner of social revolution in the capitalist west, he called for political revolution in the USSR, to restore genuine workers’ democracy in the soviets and in the state.

State-owned Economy

For a whole historic period the planned and state-owned economy that was the legacy of October remained a positive factor in the economic development of the USSR, despite the unnecessary enormity of the cost in blood and lives – measured in millions – by the mass purges, the camps and the economic mismanagement of the 1930s which led to widespread starvation. It was the planning of the economy – albeit bureaucratically-managed and wasteful – that allowed the Soviet Union to defeat Nazi Germany on the eastern front, which was the real centre of the European land war between 1941 and 1945.

As Trotsky had predicted, however, the more sophisticated and modern the economy of the USSR became, the more the bureaucracy held it back. From being a relative fetter on economic and technological development, it became an absolute fetter, until eventually it imploded economically and politically in 1989. After than point, elements of the bureaucracy, like a cross between mafioso and a kleptocracy, simply stole huge portions of the economy and what had been state-owned property and industry. Thus, the Russian ‘oligarchs’ usurped economic power from within the bureaucracy.

Trotsky’s ideas, like those of all great revolutionists, have been dragged through the mud, distorted and misrepresented in many ways in the decades since his murder in 1940. What remains of the traditions of the ‘Communist’ Parties nowadays are still steeped in a pathological distrust of Trotsky and Trotskyism, in the manner of the distortions put about in the 1930s.

In Britain, the only remnants of a once-proud Communist Party are a few old-timers who have made themselves comfortable in the bureaucracy of various trade unions and on the right wing of the Labour Party, both maintaining an unthinking suspicion of the ‘Trots’. In more recent times there has also been a myriad of petty ultra-left sects on the fringes of the labour movement who have described themselves as ‘Trotskyist’, often building an internal regime of bureaucracy that would have made Stalin proud. The defining feature of all these is a profound ignorance of the meaning of the Old Man’s writings and his work.

The best tribute we can pay to the man himself is to put aside the badges and labels, read what he really wrote and discuss the meaning of his words, their context and their applicability to modern political conditions. Trotsky made an enormous contribution to the storehouse of Marxist tradition and theory and his analysis of the rise and the meaning of Stalinism is perhaps the most important element of this. His History of the Russian Revolution and The Revolution Betrayed still stand out today as monuments of clear and profound Marxist analysis.

Marxists can also pay tribute to Trotsky by showing the same determination and courage as he showed throughout his life in the fight for socialist ideas. He has been dead now for eighty years, but his ideas are as lively and relevant today as ever. You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea.

Courtesy Left Horizons