Interview by Dayal Paleri with Mayukh Biswas (General Secretary of the Students’ Federation of India (SFI)

The country and the world are going through unprecedented and dangerous times. In India, the student community is one of the most affected groups of people. Not only has the pandemic made our lives difficult, an insensitive government has only added to all the trouble. Besides not offering measures to alleviate the severity of the issues faced by students, the government has used this crisis to implement policies and take hasty decisions that have, in contrast, enhanced the difficulty of the situation. The arrests of student activists, the push for digital education when there is a lack of necessary infrastructure, the UGC’s decision for mandatory online exams, NEP 2019 etc are only a few examples of this insensitivity.

In this timely conversation with Dayal Paleri, the General Secretary of the Students’ Federation of India (SFI), Mayukh Biswas, speaks in detail about a wide range of issues concerning the student community in the country. This includes their utter plight during the pandemic, digital education in the time of a glaring digital divide, the way forward in terms of resistance in a post-pandemic world, what the SFI has done to address these issues and more. Read on to know.

Dayal Paleri (DP): As we know, there are several existing modes of exclusion and discrimination pervasive in the realm of education, especially in higher education. Adding to that, the current pandemic and the lockdown has created a completely new set of issues to be addressed. What do you think are the specific challenges that the pandemic has posed before the student community of the country?

Mayukh Biswas (MB): Ever since the virus outbreak, the Students’ Federation of India (SFI) has been on the streets, involved in various kinds of relief activities as well as protesting against various policies of the central government. During our relief work, we witnessed how badly the marginalised were affected, especially students who constitute around 29% of our total population. A majority of them lack access not only to educational infrastructure but even to other basic necessities. During the pandemic, around 9.12 crore students have been cut off from the mid-day meal system. UNESCO indicates that almost 3 lakh children could die out of lack of food and nutrition in this situation. Students from lower primary and primary schools are suffering the most. There will also be a decline of vaccination during the pandemic due to the closure of the schools and since no alternatives have been implemented yet. However, this can be prevented. We have already demanded for an alternative approach to the current government’s lethargic policies. In a rural household, a family spends about 75% of their total income on food expenditure, and during the lockdown, around 15 crore people lost their jobs in India — who mostly work in the unorganised sector, lack minimum employment security and savings.

As researchers at the United Nations University have shown, around 100 million people could fall below the poverty line in India due to the pandemic crisis. What will happen to them and their children? This is the prime question we should discuss, which no one cares to take in mainstream media’s discourses.

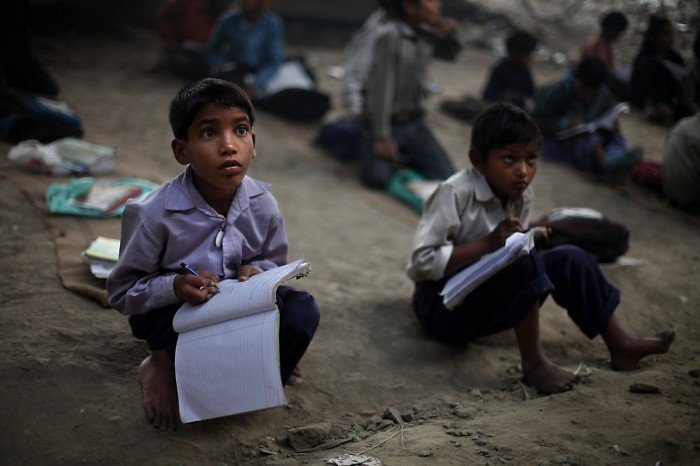

Marginalised students will suffer the most. When food and essential nutrition are denied, how will we even be able to talk about the need for online education, digital pedagogy, and the like? In a post-pandemic world, a large number of children will be compelled to turn into child labourers. The pandemic has already reached unimaginable levels.

The Prime Minister, in his Man Ki Baat, is asking students to play indoor games, stay with their families etc., while turning a blind eye to their real plight and making a mockery out of the crisis. They could have easily ensured continuous food and nutrition to the needy as there are about 7 crores 70 lakh tons of food grains stored at the Food Corporation of India. If the government is diligent, it could easily control dropout rates, malnutrition and child labour.

Despite all of this, from SFI, we will continue to raise this issue with the slogan to ‘stop children going hungry’. We are going for a nation-wide protest this month demanding sufficient supply of food to all the children in India.

DP: You have been heavily involved in relief activities in West Bengal. In that regard and also as a student leader leading a nation-wide organisation, what has your experience been during the pandemic and the lockdown?

MB: SFI has undertaken considerable efforts in various parts of India through different kinds of relief activities. As you would know, in Bengal, we had a triple challenge — firstly, the pandemic, then came the Amphan Cyclone, especially in Southern Bengal and the latest issue was the flood in Northern Bengal. Assam is also going through a similar situation. More importantly, all these crises were aggravated by the completely ineffective role and lack of intervention from the part of the state government.

The number of coronavirus-infected is rising steadily, and the actual data is still isn’t revealed by the state government. Unlike in Kerala, where the state-government is proactive in relief activities and COVID-controlling measures, Bengal is both unprotected and unassisted by the State; the government has not distributed ration or other items to the public here. On the contrary, there is a massive scam taking place beneath this crisis, especially in the ration system.

SFI has mobilised funds and distributed ration and relief materials to every household that has been affected by the triple-crisis — Our red volunteers and many IT professionals have undertaken tremendous collaborative efforts to fight this; a program was launched to conduct antibody tests in coronavirus-affected areas, without any assistance from the government. We have also taken up an effective plasma donation program for better recovery for the COVID-infected. We were able to reach the remotest of parts of the state, like the Sundarbans, which were badly affected by both the virus and Amphan. In North Bengal, where we have relatively weak organisational strength, our comrades could mobilise enough volunteers for relief work.

A woman salvages items from her house damaged by cyclone Amphan in Midnapore, West Bengal, on May 21, 2020. – The strongest cyclone in decades slammed into Bangladesh and eastern India on May 20, sending water surging inland and leaving a trail of destruction as the death toll rose to at least nine. (Photo by Dibyangshu SARKAR / AFP)

The other most valuable experience for us was the kind of response we got from the migrant workers. In that regard, I have to thank the SFI network all over the country for playing a significant role in helping them. Comrades in Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Maharashtra and even those states where we have a relatively smaller organisational network like Gujarat, they could reach out to stranded migrant workers. Interestingly, many of those workers who have reached back to their homes in Bengal, were supporters of the Trinamool Congress and anti-Left. Now, however, inspired by the intervention that the organisation was able to make for them, many have joined our democratic movement in large numbers.

Bengal has an intense unemployment crisis. In the last few years, the village economy has been completely destroyed and there is zero industrial development in urban areas. Now due to the pandemic, a large number of workers have returned to their villages, unemployed and impoverished. The TMC government has taken no active plan to rehabilitate these migrant workers who have returned in such a bad state. In fact, their economic policies are similar to that of the Modi government — subsidise the rich and ignore the poor. SFI and other Left parties have taken up several of these issues and have organised several protests against them.

DP: One of the most pertinent issues these days, regarding education, has been the push for online education and the digital divide. What is your take?

MB: Access to the internet and digital facilities are considered as basic rights in today’s world. It is as important as food, clothing and shelter. However, only a very minute section of the student community has access to the internet in contemporary India, and in this situation, online/digital education is no viable alternative to classroom education; at best, it can only be a supplement.

However, during the pandemic, most private schools, in which relatively better-off students study, have shifted to online education. In such a context, a large number of students dependent on public schools should also be provided with such facilities, and this will only be possible if the state government takes active measures to create universal access to the internet.

Kerala seems like a utopia in this regard, as the government there, with the help of the youth of the state and the voluntary associations, was able to ensure access to television to all students in the state, so that they could attend the online classes. The situation is very different elsewhere in the country — the emphasis on digital education with uneven access to it produces systematic exclusion of marginalised students. Kerala is a lone light in a sea of darkness.

One needs to locate the politics of the digital divide in the context of all the other ongoing anti-student policies of the central government. We have seen similar efforts with the recent New Education Policy as well; we have also witnessed attempts to change the syllabus to omit out crucial sections on secularism, citizenship and federalism, during the pandemic. Their ultimate aim, we must understand, is “Hindu, Hindi, Hindustan”, along with the implementation of a ‘Corporate Raj’ — we have a government which is a combination of Hindutva fundamentalism and neoliberal corporatism.

SFI has been demanding for the spending of around 6 per cent of the country’s GDP for education, but what is taking place is in stark contrast to it. In India, about 34 per cent of schools don’t have proper roofs and 16 per cent of households do not have access to electricity. This is the reality and unless we develop the necessary infrastructure, we cannot consider digital education as a viable option.

Now the UGC has released a notification directing universities to conduct online examinations. According to ICMR’s projections, the pandemic situation will worsen in the coming months. As I have already discussed, conducting online examinations is unthinkable and with the pandemic, it is difficult physically too since there is the danger of the virus spreading further. We live in a country where less than 30 per cent has access to the internet and when it comes to students, this access is only 11 per cent of it.

Think of Jammu and Kashmir, which has been put under a year-long lockdown and still survives with 2G connection. Some days ago, one of our comrades from JK had to travel down to Delhi to download some essential documents for his research purpose. Imagine the situation and the implications of the digital divide in our country! Also, even among those who have nominal access to the internet, most of them don’t have access to sufficient data to take part in online education.

We have been seeing several instances of students’ suicide or even parents’, due to their inaccessibility. In Tripura, a daily wage labourer committed suicide because he couldn’t afford a mobile phone. In Howrah, West Bengal, there was another case because she couldn’t attend online classes. The digital divide is real, and it has already contributed to a precarious situation among the marginalised student community in India.

Our slogan is that online education must not be an alternative; at best, it can only be a temporary measure. SFI has conducted surveys among students of Delhi University and Punjab University regarding the viability and accessibility to online education. In all of those surveys, students were against online education and examinations, mainly due to inaccessibility. Delhi University recently conducted an open book examination online, with the help of Amazon. We must remember that this university has students from all over India, including the remotest areas. Therefore, such a hasty measure obviously contributes to the systematic exclusion of the marginalised. Recently, Google invested a huge amount of money in digital education. In the near future, they will probably monopolise the sphere of digital education with the support from the neoliberal governments all over the world, including India.

Kerala, again, is on a different path. It is the only state where about 13 lakh students took a state-wide examination observing COVID-19 protocols and naturally, not a single student was infected. No other state has the infrastructure and commitment to take such a mammoth effort. As I have mentioned, we have a government at the centre which massively subsidises the wealthy and helping them to become wealthier, while consistently cutting down the expenditure on public education and health.

One of the most ignored, yet most important problems that will get aggravated in this period is gender violence in domestic spaces. We are a country with one of the lowest girl students’ gross enrolment ratio, which will decline further due to the pandemic. Along with it, girls and women are exposed to domestic abuses of various kinds, while being locked up in their homes with their abusers. There has already been a dramatic increase in cases of domestic violence ever since the beginning of lockdown. When SFI organised a Twitter campaign in July against gender violence, there was a tremendous response, indicating the graveness of the issue. We don’t have an IT cell or a troll army, but there still was enormous participation in the campaign because women from everywhere are facing various kinds of abuse. In addition, it is speculated by experts that child marriage and child labour among girls will also rise during this situation, unless the state intervenes.

DP: What are your thoughts on the future of education and the student movement in a post-pandemic world?

MB: In this new crisis, the neoliberal-Hindutva regime is trying to control our knowledge and capture our mind. This crisis situation has been effectively used to expand surveillance over the citizens and to crush dissent. All sorts of anti-people policies are getting implemented during this health emergency, most important of them being the relaxation of labour laws, NEP and EIA. They have also been arresting political activists, student leaders and intellectuals and all other dissenting voices. They are using this situation to curb growing discontent and resistance against the regime that got solidified as part of the anti-CAA struggles. In Pondicherry University, the administration has denied fellowship to students who took part in protests against fee hikes and CAA.

The future is indeed precarious, as the regime will continue to use this situation for deepening suppression. However, resistance will also get intensified. SFI has been organising several struggles, through various innovative means, most importantly, through the effective use of social media. We have to combine old ways of resistance with innovative means to survive this time. We must remember, this is not a new situation for. The Left has always been in the forefront fighting any crisis, be it the time of Bengal famine, the Chennai cyclone or the Kerala/Kashmir floods. Therefore, no matter how severe the current crisis is, we shall fight and shall overcome.

DP: Finally, let me come to the most crucial development in recent times — The New Education Policy (NEP 2019). SFI has raised significant opposition to NEP, arguing that it further advances the process of commercialisation, centralisation and communalisation of education. Can you elaborate on NEP’s implications and why SFI opposes it?

MB: First and foremostly, the NEP is formulated in order to reverse the progress we have made so far and to colonise our minds. In other words, it is a very ‘sophisticated’ way to push forth their agenda of centralisation, privatisation, and saffronisation of education. As I have said earlier, the government is using this health emergency to implement all kinds of anti-student and anti-people policies, as there are no parliament sessions or large scale protests now.

It is the perfect time for the regime to advance their politics — they have done extensive disinvestment and privatisation of public services, massively dilated labour laws, and lately, have been trying to implement the highly dangerous Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) 2020; the NEP is part of this larger project. They have formulated it without any consultation with state governments, students’ and other people’s organisations, or public intellectuals. They have effectively violated various constitutional provisions in trying to implement it.

The NEP will have enormous implications on multiple levels. It suggests closing down ‘small schools’ and creating a big school complex, citing economic viability. This will have adverse effects, as schools in the remotest of areas will close down and in turn, increasing drop out ratio and massively cutting down the marginalised sections’ access to schools. In the past, we have seen how a girl named Swati Pitale, the daughter of a cotton farmer in Vidarbha of Maharashtra, killed herself because she had no money for a bus ride to school. This is what will happen elsewhere in the country, if this policy gets implemented. The newly proposed school system of 5+3+3+4 and the proposed public exams in 5th, 8th and 12th grades will further enhance the strength of ‘Exam Raj’. Another crucial issue is that of the proposed collaboration with private philanthropic organisations. Who are these philanthropists? RSS owns the largest private school network in India under the umbrella of ‘Seva Bharthi’, that aims at a saffronised school curriculum. Through NEP, this project of saffronisation will be legalised and they will begin to enjoy legitimate space in India’s public school network. The NEP has also proposed a centralized mid-day meal distribution system, which will reduce the reach of the program, and could also leave the system of mid-day meals in the hands of large private networks like NGOs or religious, philanthropic organisations.

Another important issue is that the document is conspicuously silent on the question of reservation in educational institutions. SFI has been highlighting the inadequacy of the current reservation system and demanding the need for extending reservation in the private sector as well. There is no mention of gender violence and discrimination either, nor is there a mention of GSCASH.

Another significant aspect is the push for privatisation. Last year, HEFA (Higher Education Funding Agency) replaced MHRD as the funding source for infrastructural developments in IITs, IIMs and other central universities. The institutions will have to take loans from HEFA which they will have to repay with interest. Obviously, increasing fees will be the most natural way for institutes to organise funds.

The other problem in NEP is the advocacy for online education from school level on. As we have already discussed in detail, the digital divide is a harsh reality here and any attempt to push online education will further alienate those who don’t have proper access to this.

There is also a clear attempt to centralise the education system through the Rashtriya Shiksha Ayog. There won’t be an election to RSA and all the members will be appointed by the regime without any accountability. Through RSA and the proposed National Research Foundation, the government will be able to prioritise the kind of research that takes place in universities and other institutes, which will visibly undermine academic freedom and autonomy. Research that suits the interests of the political regime will be funded (perhaps those looking to find ways to extract “gold from cow piss”), while original, scientific and social science research will not be.

There is a proposal in the NEP to reduce the content of syllabuses. This will obviously mean slashing chapters on secularism, federalism, the national movement, the constitution and any other thing that comes in the way of the current regime.

There is a lot of emphasis on training students in ‘Sanskrit’, while other classical languages like Urdu are not given any significance.

There is also an unusual emphasis on vocational training throughout the policy. There is a provision for internship for school children of class 6th and 8th as part of the proposed curriculum. This is dangerous as it will push many students back to their caste-based occupations or some kind of child labour, turning out to be a gross violation of the Child and Adolescent Labour Prohibition and Regulation Act of 1986. This internship will be a ‘legitimised’ exit from school education towards child labour for many.

The NEP also mentions a ‘multidisciplinary’ approach — but we must be sceptical towards that, since we fear that it will completely obliterate the need for specialised disciplinary learning as a basis of knowledge production. Our contention is that the aim of the NEP is not to cultivate people who would be involved in knowledge production. Instead, would produce skilled labour suitable for the demands of the market, and therefore, the over emphasis on vocational training. Remember, India’s educational market is larger than that of Europe!

This sort of an education will create a generation who will be the jacks of all trades and masters of none. In fact, this is very similar to the colonial model, where the purpose of education was to find labour for the colonial regime. There are a lot more issues as well. The policy is silent on the rights of disabled students; there is no mention of campus democracy, and hence, no way to ensure the rights of students.

It has been receiving huge praise for keeping aside 6 per cent of GDP for education, while it has been SFI’s long-standing demand. In fact, the NEP spending 6 per cent of GDP is a directive for state and central government which has been there in all previous policy recommendations, but was never implemented. In total, the NEP is an extremely regressive policy document that nakedly violates several constitutional values of the country. There is a lot of emphasis on fundamental duties, but none on fundamental rights. It is due to these reasons that SFI is vehemently opposed to the NEP and will certainly continue our fight to restore and advance the progress that we have made so far in the field of education.

Courtesy Student Struggle