By Sam Miller

Stalin’s bureaucratic dictatorship assassinated Leon Trotsky 80 years ago. What many may not realize, however, is that it also killed all of his children.

Leon Trotsky’s assassination was painful, gory, and orchestrated by Stalin. What many may not realize, however, is the extended torture that Trotsky’s children suffered at the hands of the bureaucratic dictatorship, eventually leading to all of their deaths. On the 80th anniversary of Trotsky’s assassination, we should not only honor his revolutionary spirit, but also the life and sacrifice of his children. Stalin’s hateful and violent pursuit of the Trotsky family was motivated not only by his personal vendetta against Trotsky, but also by his desire to crush all attempts of the Fourth International to spark world revolution and overthrow his counterrevolutionary dictatorship.

Trotsky’s Murder

In January of 1937, Trotsky and his wife Natalia arrived in Mexico City. Trotsky’s friend and well-known painter Diego Rivera lent him a house in Coyoacán. It is no exaggeration to say that Mexico was the only government in the world willing to accept Trotsky at this point. He had been exiled numerous times, pushed to various corners of the world at Stalin’s command. But he wasn’t safe for long. Almost four years after his arrival, Trotsky would be targeted for assassination by the G.P.U., the Stalinist secret police.

Trotsky began May 24, 1940 the same way he spent other mornings in Mexico City: by walking the grounds, looking for different types of cacti, and feeding the chickens and rabbits. He would then retreat to his study for hours of thinking, reading, writing, and meeting with comrades to discuss politics and revolution. That evening, after a long day of work, Trotsky, who suffered from insomnia, took a sleeping pill. Hours later, he was jolted awake in the middle of the night by the pounding sound of hundreds of bullets firing directly towards him. It was soon after this brutal attack that Trotsky would learn how Natalia saved his life that night.

As soon as the attack began, Natalia jumped out of bed and moved Trotsky to safety. They hid together underneath the bed as machine guns fired rounds of ammo and attempts were made to blow up his library and his writings. Natalia describes the murderous arsenal of the assassins as follows:

Hundreds of spent cartridge cases, several detonators, seventy-five cartridges, an electric saw, twelve sticks of dynamite, electric fuse-wire for the explosives and the two incendiary bombs were taken away.

Trotsky knew that he was a constant target for Stalin, and that he would be hunted down with a vengeance. He predicted that there would be further attempts to take his life, and he was right. What Trotsky didn’t expect was that an odd fellow named Ramón Mercader, who was living under the pseudonym Jacques Mornard and was dating Trotsky’s secretary Sylvia Ageloff, would be the one to finally kill him. Mercader pretended to sympathize with and support Trotsky’s views so as to not seem suspicious or raise any cause for concern.

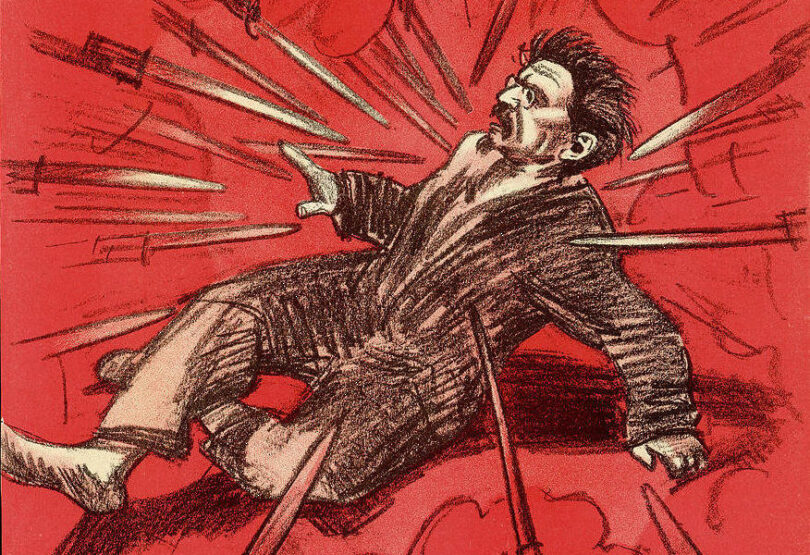

On August 20, 1940, Trotsky was back to his daily routine of enjoying nature and writing about politics. Mercader had asked to meet with him that evening to show him an article about James Burnham and Max Shachtman. Trotsky obliged, though Natalia notes that he would have rather stayed in the garden, feeding the rabbits or left to himself; Trotsky always found Mercader to be a bit off and irritating. Natalia accompanied the two men to Trotsky’s study and left them there. She found it bizarre that Mercader was wearing a raincoat in the middle of summer. When she asked him why he was wearing it along with rainboots, he replied curtly, (and for Natalia, absurdly), “because it might rain.” No one knew at the time that the murder weapon, the ice axe, was concealed underneath the raincoat. Within a matter of minutes, a piercing and terrifying cry could be heard from the next room over.

Natalia recollects the horror of hearing her husband screaming in agony. “Three or four minutes went by…I was in the room next door. There was a terrible piercing cry…Lev Davidovich appeared, leaning against the door frame. His face was covered with blood, his blue eyes glistening without spectacles and his arms hung limply by his side…”

Leon Trotsky had been fiercely struck in the head with the blunt end of an ice axe, penetrating his skull three-inches deep. He was rushed to the hospital, where he died the next day. Even in the midst of unbearable pain and the certainty that he would die, Trotsky found humor. Natalia recounts: “A nurse started to cut his grey hair. Leon Davidovich smiled at me and whispered, ‘You see, here’s the barber.’ We had spoken that day of sending for one…”

Trotsky’s Children

Trotsky’s death marked the cumulation of more than a decade’s worth of torture, harrassment, and murder of the Trotsky family at the hands of Stalin. Trotsky outlived all four of his children, something a parent should never have to suffer. In order to grasp the overall tragedy of Trotsky’s murder, it is important to understand the persecution and torment that his children suffered for many years.

Trotsky had four children: two daughters, Nina and Zinaida (Zina), with his first wife Aleksandra Sokolovskaya; and two sons, Lev and Sergei, with his second wife Natalia Sedova. None of these children would escape Stalin’s wrath.

Zina

Zinaida and her father had great affection for one another. Of all Trotsky’s children, Zina resembled him most in both physical appearance and emotional intensity. Zinaida looked up to Trotsky and craved his love and approval throughout her entire life. She was a Marxist and Trotsky’s first daughter. Shortly after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Zina married Zakhar Borisovich Moglin. In 1923, Zina and Moglin had a daughter named Alexandra Moglina. Just a few years later, the two divorced. After her divorce from Moglin, Zina remarried Platon Ivanovich Volkov, a member of the Left Opposition. They had a son named Seva (who is known today as Esteban Volkov).

It was very difficult for Zina to be away from her father, and life became much harder when she contracted tuberculosis. In January 1931, Joseph Stalin permitted Zina to leave the Soviet Union and join her father in exile, but only allowed her to bring one other person. She chose her youngest child, her son Seva. Zina and her son stayed with Trotsky and his wife, Natalia, in Turkey until November of 1931. Zina had to leave her daughter Alexandra behind, who stayed with her father, Moglin, for a year until he was arrested. At that point, Alexandra was cared for by Zina’s mother, Alexandra Sokolovskaya.

During her time in Prinkipo with Trotsky, Natalia, and her son Seva, Zina suffered from unbearable depression. She missed her daughter Alexandra, and couldn’t stand being separated from the girl. She also missed her husband, Seva’s father, an open and outspoken Trotskyist, who had been arrested in 1929 and deported to Arkhangelsk.

To make matters worse, Zina didn’t feel the same closeness with her father that her brother Lev did. She was intensely jealous of their closeness and their comradeship. She wished to be Trotsky’s most trusted confidant, but Trotsky was not interested. Trotsky told Zina that, for her own safety, it was best for them to not collaborate closely on politics, bearing in mind her plan to return to Moscow and reunite with her family. He sensed her instability and insisted she rest and get the medical help she needed. At one point, he even suggested that she go to Berlin for psychoanalysis. She initially refused, until she finally agreed. Zina stayed with Trotsky and Natalia in Turkey for ten months before relocating to Berlin to treat her illnesses, leaving Seva in her father’s care.

In February of 1932, news came that Stalin forbade all of the Trotskys in exile from returning to the Soviet Union. Zina now knew that there was little to no hope of her ever reuniting with her daughter, her husband, and her mother Alexandra. Zina experienced nervous breakdowns, becoming more and more unwell and unable to care for herself. Suffering from extreme depression and worsening consumption, Zina committed suicide on January 5, 1933.

Before her death, Zina underwent multiple operations on her lungs in an attempt to improve her physical health, but to no avail. As her mental health continued to dwindle, she was treated by psychologists. Her doctor made the strong recommendation that returning to Russia to reunite with her family would be the best course of action to improve Zina’s overall well-being. But Stalin’s malice and vindictiveness had no limits, and he deprived Zina from the one thing that would have given her a fighting chance at life: her family. Desperate and alone, Zina ended her life at her home in Berlin by inhaling gas. It was Stalin’s cruelty that broke her spirit and stripped her of any will to live.

Nina

Another contributor to Zina’s depression was the death of her younger sister, Nina, who passed away from tuberculosis on June 9, 1928, at just 26 years old. Nina, though just a young woman, was not spared from Stalin’s abuses either. As a young child, Nina and her sister were raised mostly by their paternal grandparents, David and Anna Bronstein. Their mother and father — Trotsky and Alexandra — separated in 1902 and spent much of their time as revolutionaries living in different countries and hiding from tsarist authorities.

Nina married her husband Man Samoilovich Nevel’son, with whom she had two children: a son named Lev Manovich Nevel’son, born in 1921, and a daughter named Volina Mannovna Nevel’son, born in 1925. Her husband, an active supporter of Trotsky’s Left Opposition, was arrested and sent to a labor camp in Siberia. Nina, also very active in the Opposition, had been expelled from the party and lost her job. Once she became ill with tuberculosis, she had great difficulty receiving proper medical care because she was Trotsky’s daughter. After Zina took care of her for three months, Nina died in her arms. Zina sent a telegram to her father in exile, telling him that Nina was calling for him constantly; it took 43 days to arrive.

Nina was 26 years old when her life came to an end. Of all of Trotsky’s children, she was the youngest to die. Her two surviving children were cared for by her mother, Alexandra Sokolovskaia. After the arrest of Alexandra in 1935, Nina’s children were placed in the care of Alexandra’s ill sister, who lived in Ukraine. Both children disappeared without a trace, their fate unknown.

Despite many years of persecution at the hands of the Stalinist bureaucracy, neither Nina nor Zina should be reduced to their sufferings. Both women were committed revolutionary Marxists who fought for the authentic legacy of the October Revolution. We should remember their efforts to create a better world and not see them as characters in a melodramatic soap opera.

Sergei

Trotsky and Natalia’s youngest son was named Sergei Sedov, born in 1908. Growing up with Trotsky, Natalia, and his older brother Lev was quite eventful. Trotsky and Natalia often discussed atheism at home, and held a certain disdain for what they called “the orgy of present-giving” at Christmas. In fact, the young boys only learned who the Virgin Mary was once they began attending a local Christian school. When Sergei was but a young boy, he once blurted out “There’s no God and no Santa Claus!” in public.

By the time Sergei turned 16, he was the most rebellious of the Trotsky children, rejecting what he considered to be his parents’ “bourgeois” tastes. As he grew up learning about socialist equality, he rejected even the smallest forms of privilege, including the opportunity to wear nice clothes or be seen before others at the doctor’s office. With a head full of ideas for a new life, he left home and surprised many by deciding to join the circus. Eventually, he started coming back to visit his parents once a week, but continued to reject their financial offerings.

Of all Trotsky’s children, Sergei was the least involved with official politics. His passion was science, including engineering, thermodynamics, and diesel engines. He became a professor at the Higher Technological Institute in Moscow, where he lectured on various science-related subjects. But it would be wrong to think Sergei was simply a mild-mannered academic. There is one episode in particular when Sergei valiantly defended his father. As the newly exiled Trotsky was being dragged off by Stalin’s men at the Kazan station, Sergei stood up for his family and exchanged blows with a G.P.U. agent.

On August 3, 1935, Sergei was viciously uprooted, arrested, and sent from Moscow to Siberia. By this time, he had fallen in love with Genrietta Rubinshtein, who was keen to follow him to Siberia, but Sergei shouted to her from his cell to go back to Moscow for her own safety. He was shortly released from imprisonment and permitted to find employment in Siberia, where his skills meant he could work in the goldmine industry. Back in Moscow, Genrietta gave birth to their daughter Yulia in 1936. One year later, Genrietta was arrested for no other reason than being Sergei’s lover, and their daughter was raised by Genrietta’s parents. Yulia never met her father, and she would go on to endure years of suffering as a consequence of her father’s name.

During the initial phase of Stalin’s Great Purges in 1936, Sergei was rearrested and sent to a labor camp. In 1937, he was shot and killed at the age of 29. Even though Trotsky’s son tried to separate himself from politics, he could not escape Stalin’s murderous bureaucratic grip.

Lev

Trotsky was closest with his first son, Lev Sedov, born on February 24, 1906. Lev developed a serious interest in politics from a young age, and went on to become one of Trotsky’s closest collaborators, contributing a great deal to many of his greatest works. As Trotsky himself said, “My son’s name should rightfully be placed next to mine on almost all my books written since 1928.” Lev was a leader of the Trotskyist movement in his own right, and vehemently opposed Stalin until the day he died.

In order to join the Komsomol, the Young Communist League, Lev lied about his age, claiming to be 14 instead of 13. He joined in their campaign to help organize bakery workers. During the civil war, at only 13, Lev accompanied his father to the Polish front; like Trotsky, he sported a leather jacket, a common fashion staple amongst the Bolshevik leaders. In 1925, at the age of 19, Lev married Anna Samoilovna Riabukhina. They had a child together named Lev L’vovich Sedov, born in 1926.

Lev accompanied his parents into their exile at the end of the 1920s for a brief period. But in 1931, he obtained a German visa to attend a Technische Hochschule in Berlin. There, he studied physics and mathematics, though his primary focus remained politics. From 1923 onwards, Lev fully devoted himself to his father’s cause, becoming a leading presence in the Left Opposition. As the G.P.U. and Stalin understood, Lev was Trotsky’s right-hand man and de facto chief-of-staff.

Unlike Zina’s extroverted and passionate demeanor, Lev resembled his mother more than his father. He was gentle, quiet, but also even-tempered and modest. Lev’s political work exhibited all the marks of absolute dedication and commitment to the revolutionary struggle against Stalinism. Trotsky relied on his son, and often the relationship was strained by Trotsky’s own demands and overbearing attitude. Trotsky had high expectations for Lev, but he also wanted his son to remain independent. This was a contradictory and codependent dynamic: the more Lev gravitated towards his father, the more Trotsky resented him. However, the more emotional space Lev took, the more anxious and angry Trotsky became. This created a strain between the two men, but their bond was strong enough to overcome such emotional tensions.

Lev was overscrupulous with money, giving all of his funds to manage the Left Opposition’s Bulletin, leaving barely anything for himself. He would also send money to his wife and son back in Russia, who were suffering from poverty. Lev would roam the streets of Berlin at night, hungry and afraid of becoming a G.P.U. target. Over time, his insomnia would only get worse, taking a massive toll on his health.

With the rise of Hitler, the Bulletin was soon banned in Berlin, forcing Lev to go into hiding. The leadership of the Opposition moved to Paris in 1933, where Lev played a leading role. In the first Moscow Show Trial of 1936, Lev and his father were indicted in absentia on charges of treason and conspiracy. If the G.P.U. ever managed to kidnap father and son, they would be quickly sentenced and executed, along with all the other Old Bolsheviks that Lev grew up with.

The campaign against the show trials fell to Lev himself, and he wrote the first systematic refutation of the prosecutor Andrey Vyshinsky’s lies. The facts about these frame-ups were presented in Lev’s work, The Red Book: On The Moscow Trials. Trotsky praised the work as a tour de force of bravery, exclaiming that in his son, “we have a defender.”

Despite refuting all the falsehoods of the Stalinist regime, the G.P.U. still hounded and shadowed Lev constantly. Besides Trotsky, he was the most wanted individual marked for death. With tragic and deadly consequences for Lev, he befriended Mark Zborowski, who was operating under the alias Étienne. Lev put all of his trust into this man, who turned out to be an agent provocateur for the Stalinists. Zborowski fed the G.P.U. a consistent stream of information about the Left Opposition’s plans, and details about Lev’s own personal struggles with illness.

Towards the end of a long decade of what Victor Serge called his “infernal life” of suffering, Lev could no longer put off surgery for an appendectomy. Zborowski informed the G.P.U. of exactly where Lev would receive treatment. The hospital’s own staff consisted of Russian emigres, which in retrospect was suspicious to Trotsky and others. After the operation, Lev was thought to be on the road to recovery. But soon, his health rapidly deteriorated, and after a second surgery, he died on February 16, 1938. Much circumstantial evidence points in the direction of foul play, but nothing has been absolutely proven that the G.P.U. murdered Lev. Nevertheless, one can say for certain that years of harassment, threats, and psychological torture helped lead to this point.

The Future Belongs to the Children

In James Cannon’s funeral oration for Trotsky, he asked the listeners to consider the following:

When Marx died in 1883, Trotsky was but four years old. Lenin was only fourteen. Neither could have known Marx… Yet both became great historical figures because of Marx, because Marx had circulated ideas in the world before they were born. Those ideas were living their own life… So will the ideas of Trotsky, which are a development of the ideas of Marx, influence us, his disciples, who survive him today. They will shape the lives of far greater disciples who are yet to come, who do not yet know Trotsky’s name. Some who are destined to be the greatest Trotskyists are playing in the schoolyards today. They will be nourished on Trotsky’s ideas, as he and Lenin were nourished on the ideas of Marx and Engels.

On the 80th anniversary of Trotsky’s assassination, we recognize the ways in which his ideas and revolutionary convictions shaped and influenced many who came after him, and many who are still yet to come. Trotsky had several grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great-grandchildren, some of whom still live today to continue his legacy. Zina’s son, Esteban Volkov, now 94 years old, is the current custodian of the Trotsky Museum in Mexico City.

We honor the ways in which each of Trotsky’s children lived and fought against Stalinism with dignity. Today, we continue their fight against fascism and opportunism in favor of the international working class.

Courtesy Left Voice